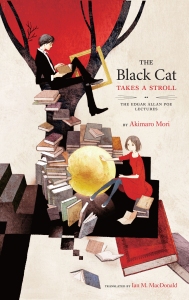

Title: The Black Cat Takes a Stroll: The Edgar Allan Poe Lectures

Japanese Title: 黒猫の遊歩あるいは美学講義 (Kuroneko no yūho arui wa bigaku kōgi)

Author: 森 晶麿 (Mori Akimaro)

Translator: Ian M. MacDonald

Publication Year: 2016 (America); 2011 (Japan)

Publisher: Bento Books

Pages: 146

Let me preface my review of The Black Cat Takes a Stroll by saying that this book is misogynistic pseudo-intellectual garbage.

I’ve tried to keep my tone sane and reasonable, but I don’t want to mislead anyone into wasting their time reading about something that celebrates notions of male dominance and superiority. If you know this sort of thing won’t appeal to you, it’s probably best to skip this review.

The Black Cat Takes a Stroll is a collection of short horror-themed mystery stories centered around “the Black Cat,” a genius 24-year-old professor. The narrator is a first-year PhD student specializing in Western literature. She became friends with the Black Cat when the two were undergraduates together, but now the narrator is the Black Cat’s personal assistant, or “sidekick,” as she calls herself. She has decided to write her dissertation on the work of Edgar Allan Poe, and the book opens with the Black Cat mansplaining the narrator’s research to her.

This is how each of the six stories in the book plays out: something strange happens within the narrator’s circle of friends and acquaintances, she doesn’t understand what’s going on, and so she goes to the Black Cat, who delivers a condescending lecture about literature and philosophy. The mysteries are bizarre and absurd, and they tend to be more reminiscent of the “erotic grotesque nonsense” of the Shōwa-era dark fantasist Edogawa Ranpō than they are of the dark yet largely linear logic of Edgar Allan Poe, yet the Black Cat still draws on his knowledge of European intellectual traditions to explicate the psychology of the people involved.

In the first story, “To the Moon and Back,” the narrator has come into possession of a hand-drawn map that doesn’t seem to correspond to the neighborhood it purports to represent. Although the provenance of this map clearly suggests the circumstances of its creation (the narrator found it carefully preserved and tucked away in her mother’s dresser drawer, which would lead most people to the immediate conclusion that it was given to her by a former lover), the Black Cat is more interested in discussing abstractions relating to mapmaking. His mental process is explained by the narrator as follows: “Applying Bergsonian aesthetics to literary criticism is the Black Cat’s specialty. Upon returning from Paris, he published a paper titled, Dynamic Schema and the Poetry of Stéphane Mallarmé that caused a sensation” (12). Through a series of complicated mental gymnastics, the Black Cat is able to apply a diluted mishmash of schema theory to arrive at the obvious conclusion, ie, the secret letter in the narrator’s mom’s underwear drawer is from the narrator’s mom’s secret lover. Good job, son! Handshakes all around.

The more intriguing story underneath the plot of “To the Moon and Back” concerns why the narrator’s mother had a secret lover to begin with. According to the narrator, her mother is a successful academic specializing in Japanese literature, a job that has not been easy for her. As the narrator says, “Japanese universities are feudal institutions. To succeed in the ivory tower of academe, a woman has to work at least twice as hard as her male colleagues – which only makes my mom seem that much more amazing” (15). Because the narrator has entered graduate school because of her respect and admiration for her mother, I wanted to know more about this woman and her relationship to her daughter, but the author never allows the narrative focus on the Black Cat to waiver for more than a few paragraphs.

This is a major shortcoming in all of the stories in the collection, in which female characters function solely as plot devices and abstract concepts for the Black Cat to play with. To add insult to injury, the Black Cat loves to cite real-life Western scholars and theorists, but never in the entire book does he mention an actual female writer.

I mean listen, we’ve all read Sherlock Holmes and watched the Iron Man movies, and we all love narcissistic yet brilliant male characters, but the misogyny underlying The Black Cat Takes a Stroll frequently results in awkward and uncomfortable situations that serve to underscore the author’s disdain for women. To give a representative example, in the fourth story, “The Hidden Flower,” the Black Cat manipulates the narrator into a situation in which she will be raped by his uncle so that he can prove a point to her. His uncle doesn’t take the bait, and so the Black Cat brings the narrator home with him and hypnotizes her so that she won’t remember what happened. He can’t stop himself from bragging about the incident after the fact, however, because he still wants the narrator to understand the point he’s trying to make. Instead of being like, “Wow, it’s super not cool that you set me up to be sexually assaulted for the sake of winning an argument and then tried to gaslight me,” the narrator is comforted by the level of control the Black Cat is capable of exerting over her. At the end of the story, she says, “My head slumps onto the Black Cat’s shoulder. Safe and secure, I feel I could sleep forever” (96-7).

It’s entirely possible that I could be misreading or overreacting to “The Hidden Flower,” but honestly, I’m not too terribly interested in going through it again. In any case, this is merely one of the many examples of the Black Cat’s patronizing attitude regarding the narrator and her subsequent worship of him. Here’s another example from the first page of the story…

This stuff crumbles the moment I touch it with my chopsticks. Sesame tofu isn’t meant to crumble. It’s supposed to be gooey. I’m baffled.

“A bit like the paper you just presented,” observes the Black Cat seated beside me. He’s alluding to the fiasco that I’ve just succeeded in putting out of my mind. The guy is a fiend – a genius, true, but nonetheless a fiend. Then again, maybe that’s the nature of geniuses. (73)

No, no it’s not. This guy is nothing more than a garden-variety asshole, and it’s painful to see the narrator fawn over him.

The Black Cat Takes A Stroll is an unironic romanticization of male misogyny within an academic context, and I hated every page. If you’re a woman who has seen male colleagues promoted ahead of you, and if you’re sick of being told your business by insufferable male douchebags, and if you’re frustrated by the societal assumption that men know more about your mind and body than you do, then the stories in this collection might hit a little too close to home. The gut punches this book delivers are frequent and unyielding, and I couldn’t read more than five pages at a time. Even if you’re not as sensitive to overt sexism as I am, I still don’t think the mysteries presented by the author (such as the mystery of the letter in the mother’s underwear drawer) are all that original or compelling.

I’m happy to see that a book like The Black Cat Takes a Stroll has been published in English translation – it’s good to see work coming out that isn’t associated with the current big names familiar to English-language readers. It’s also wonderful that novella-length genre fiction from Japan is finding its way into English, and I think that Bento Books is doing something interesting and important. Still, between misogynistic light novels and misogynistic suspense fiction, I feel that there’s a definite bias in the material that has come out in the past few years, and The Black Cat Takes a Stroll doesn’t add anything new to the landscape of contemporary Japanese fiction in translation.

Review copy provided by Bento Books.

Reblogged this on Medieval Otaku and commented:

A great review of a flawed book. Stephen King says that aspiring authors should read bad books now and then to build confidence that one can get published, and this book sounds perfect for that.

Even though you prefaced this with “if this doesn’t sound like your kind of book, you can skip this”, I read all the same because I was intrigued by how it was so misogynistic and awful. I was not disappointed! I enjoyed the combination of the analysis of the text and its narrative, as well as the gross messages it put forth, and in particular, I really loved the line “No, no it’s not. This guy is nothing more than a garden-variety asshole”. Perfect! I am very grateful for this review, so I won’t accidentally discover this book in a shop and waste my time on it.

Like Annabelle, I couldn’t help but read through the rest of your review just to see how bad it could possibly be. Besides, it’s always a pleasure to read your reviews, even if I wouldn’t touch the book with a ten foot pole! It’s a shame this book is so awful, as I also appreciate what Bento Books is trying to do…

Thank you so much for your comment! And I agree with you that Bento Books seems like they’re trying to do something really cool. There are some really great people who worked on this book, you know?

I wonder what the story behind this publication is. Did the editors not notice the misogyny? Or did they think something along the lines of, Well, this is popular culture, of course it’s going to be misogynistic, no one will care? Or did they get pushed into a contract in which the Japanese press said that they had to publish this book if they wanted to get the translation rights to something else? If the latter is the case, did they specifically send a review copy to me because they knew I would call out this book for being disgusting…?

If nothing else, I hope Bento Books will consider publishing genre fiction by female authors in the future.