This essay contains spoilers for the completed series.

Takeuchi Naoko’s shōjo manga Pretty Guardian Sailor Moon, which began serialization in 1991 in Kōdansha’s shōjo magazine Nakayoshi, was a truly transformative work. Not only was it an incredible inspiration for other manga artists, but manga editors and anime studio executives also started aggressively mixing and matching the elements of Sailor Moon to create derivative works such as Wedding Peach and Kamikaze Kaitō Jeanne. Meanwhile, popular anime franchises like Tenchi Muyō! quickly developed magical girl spin-off series. Unfortunately, many of these new magical girl series merely regurgitated different aspects of Sailor Moon in an endlessly looping cycle of character tropes and plot devices. Thankfully, Magic Knight Rayearth, one of the very few magical girl series from the nineties to survive without ever going out of print in Japan, effectively broke the cycle of narrative consumption and reproduction, both for its creators and for its audience.

In order to capitalize on the success of Sailor Moon, the editorial staff of Nakayoshi hired the fledgling creative team CLAMP, whose debut series RG Veda was enjoying a successful run in a monthly Shinshokan publication called Wings, which also targeted a shōjo audience. Like Sailor Moon, Magic Knight Rayearth is a shōjo manga featuring many conventions of the mahō shōjo, or magical girl, genre. For example, its three heroines are equipped with fantastic weapons and garbed in middle school uniforms that undergo a series of transformations as the girls become more powerful. Also, like Sailor Moon and her friends, the heroines of Magic Knight Rayearth are able to attack their enemies and heal their injuries with flashy, elementally based magic spells.

Magic Knight Rayearth draws clear influences from other genres besides mahō shōjo, such as mecha action series for boys and video game style fantasy adventure. Over the course of their adventures in the fantasy world of Cephiro, the three protagonists of Magic Knight Rayearth must revive three giant robots called mashin, which will aid them in their final battle against the mashin of their enemies. The sword-and-sorcery elements of the title seem to be borrowed directly from adventure series such as Saint Seiya and Slayers, and the manner in which the weapons, armor, and magic of the three heroines “level up” through the accumulation of battle experience is a feature drawn from role-playing video games like Final Fantasy and Dragon Quest. Although Magic Knight Rayearth seems to have been shaped from a high concentration of elements drawn from genres targeted at boys, its ornate artistic style, narrative focus on the friendship between three adolescent girls, and guiding theme of romantic love place the work firmly in the realm of shōjo manga.

The character tropes represented by the three heroines of the series are also common to shōjo manga. Hikaru, the leader of the team of fourteen-year-old warriors, is extraordinarily innocent. She never hesitates to help her friends despite the danger to herself, and she trusts others implicitly. No matter what perilous circumstances the girls find themselves in, Hikaru’s hope, trust, and naivety are unflinchingly portrayed in a positive light. Umi, a long-haired beauty, is an ojōsan, or young lady, from a rich family. As such, she is used to getting her way and a bit more willing to question her circumstances and the motivations of others. Instead of being portrayed as experienced and savvy, however, Umi’s skepticism comes off as foolish and bratty; she endangers her two friends and must be gently put back into line by Hikaru’s emotional generosity. Fū is the meganekko, or “girl with glasses,” of the group. As such, she is demure in her interactions with other characters and speaks in an unusually formal and polite manner. Fū is enrolled in one of the most prestigious middle schools in Tokyo, and the other characters occasionally comment on how intelligent she is. Although Fū does indeed manage to solve a few of the riddles the three girls encounter in Cephiro, her common sense and deductive skills are no match for the pure heart and magical intuition of Hikaru. Like Sailor Moon, Magic Knight Rayearth valorizes girlish innocence, trust, and emotional openness. All obstacles may be overcome by the power of the friendship between a small group of teenage warriors, whose battle prowess derives not from training or innate skill but rather from the purity of their hearts.

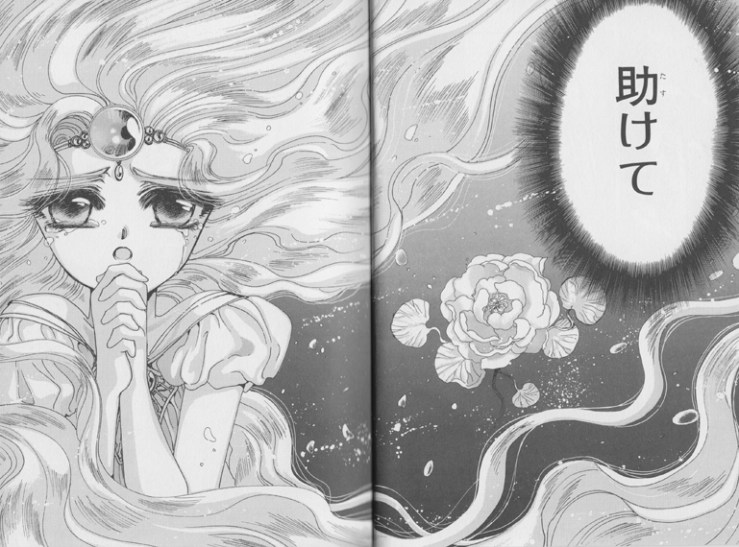

Hikari, Umi, and Fū are summoned from Tokyo to the fantasy world of Cephiro by a fellow shōjo, Princess Emeraude. The opening page of the manga presents the reader with a single glowing flower suspended in space. At the heart of this flower is a young girl with long, flowing robes and hair. The following page reveals that she is crying. “Save us” (tasukete) are her first words; and, as she summons the Magic Knights, a beam of light emerges from a glowing jewel that ornaments the circlet she wears. In a two-page spread, this girl looks directly at the reader, still entreating someone to “save us.” This girl is Princess Emeraude, the “Pillar” (hashira) who supports the world of Cephiro. In Cephiro, one is able to magically transform the world according to the power of one’s will. Emeraude, who possesses the strongest will in Cephiro, maintains the peace and stability of the world through her prayers. Unfortunately, since she has become the captive of her high priest, an imposing man in black armor named Zagato, Emeraude is no longer able act as the pillar of Cephiro, and the world is crumbling. She thus summons the three Magic Knights to save her and, by extension, Cephiro.

Princess Emeraude is the quintessential shōjo. She is delicate, fragile, and beautiful, just like the flower in which she is imprisoned. She is gentle and kind, yet possesses a great strength of will. Her undulating robes and hair associate her with water, and it is suggested that she is imprisoned beneath the sea. Like water (which is often associated with femininity in anime and manga), Emeraude is outwardly weak and attempts to exert her will through nonviolent methods. Her wide eyes, which are often brimming with tears, reflect the open and unguarded state of her interior world, and she innocently trusts the Magic Knights while still attempting to see the goodness within the man who has supposedly imprisoned her. Princess Emeraude is similar in both appearance and disposition to Sailor Moon‘s Princess Serenity, who also embodies the shōjo ideal of gentle compassion.

In Beautiful Fighting Girl, Saitō Tamaki explains that “subcultural forms […] seduce and bewitch us with their uncompromising superficiality. They may not be able to portray ‘complex personalities,’ but they certainly do produce ‘fascinating types.’ The beautiful fighting girl, of course, is none other than one of those types.” Hiraku, Umi, and Fū are beautiful fighting girls (bishōjo), and Princess Emeraude is a classic damsel in distress. Yet another of the “fascinating types” common to anime and manga is the demonic older woman, the shadow cast by the unrelenting purity of the shōjo. As a psychoanalyst, Saitō identifies this character type as the phallic mother, an expression “used to describe a woman who behaves authoritatively. The phallic mother symbolizes a kind of omnipotence and perfection.” Words like “omnipotence” and “perfection” just as easily describe characters such as Hikaru (or Sailor Moon); but, in the realm of shōjo manga in particular, these qualities become extremely dangerous when applied to adult women. The concept of “phallic” is of course threatening (heavens forbid that a woman have the same sort of power and agency as a man), but so too is the concept of “mother.” In her discussion of shōjo horror manga, Hiromi Tsuchiya Dollase notes a clear trend concerning the abjection of the mother, especially through the narrative eyes of daughters, who “have seen the struggle of their mothers and the tragedy that they endured in patriarchal domesticity.” For a teenage female audience, then, an adult woman is both a frightening and pathetic creature. Her mature adult body has already passed its prime, her anger and frustration can change nothing, and any power she wields is capricious and often misdirected. For such a woman, who has lost both her innocence and her emotional clarity, power is a dangerous thing that dooms her to the almost certain status of villainhood.

The three heroines of Magic Knight Rayearth must fight two such women in order to save Cephiro. The first of these women, Alcyone, is a twisted perversion of Princess Emeraude. Like Emeraude, Alcyone is associated with water. We first see her emerging from under a waterfall, and her long hair and cape cascade around her body as Emeraude’s do. Alcyone has a large, circular jewel ornamenting her forehead as Emeraude does; and, like Emeraude, she possesses and strong will and is skilled in the use of magic. Unlike Emeraude, however, Alcyone is evil and must be defeated by the Magic Knights. The primary difference between Alcyone and Emeraude is that, while Emeraude is portrayed as an innocent child, Alcyone radiates an adult sexuality, which is apparent in her revealing costume and condescendingly flirtatious dialog. Alcyone attacks the Magic Knights on the orders of Zagato; and, after she is finally vanquished, it is revealed that Alcyone is in love with him. This sexually and emotionally mature woman is characterized as evil, then, simply because she is in love with a man she cannot have. The long, jewel-tipped staff that Alcyone carries and the ornamentation on her armor mark the character as a phallic mother, or a powerful woman who is ultimately rendered pathetic because of her inability to successfully wield her power to attract the attention of the man she loves.

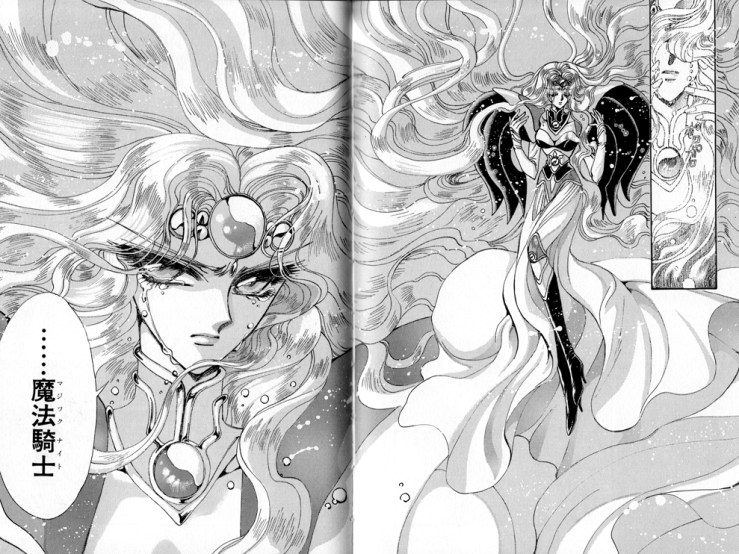

In the final pages of Magic Knight Rayearth, Hikau, Umi, and Fū must fight Emeraude herself, for Emeraude is also in love with Zagato. Because she has fallen in love, Emeraude’s purity of heart and strength of will are compromised, and she can no longer act as the Pillar of Cephiro. Since no one in Cephiro can kill her, and since she cannot kill herself, she has imprisoned herself and summoned the Magic Knights so that they may save Cephiro by destroying her and thereby releasing her from her responsibilities, for it is only with her death that a new Pillar can support Cephiro. By falling in love with a man, Emeraude has renounced her pure shōjo status. When the Magic Knights finally find her, the princess no longer appears as a child but has instead taken on the body of an adult woman. Emeraude’s adult body represents both her selfishness – her wish to devote herself just as much to her personal desires as to the welfare of the wider world – and her willingness to use her immense power in order to achieve her “selfish” goals. The two-page spread in which the reader first encounters Emeraude as an adult mirrors the pages in which Emeraude first appears as a child. Emeraude still floats in a watery space, and she completes her first phrase, “Please save us” with the target of her plea, “Magic Knights.” Instead of appearing metaphorically as a flower, however, Emeraude’s full body is displayed, and her white robes are accented with black armor. Emeraude has thus been transformed into a phallic mother like Alcyone, and the tears in her eyes represent her anger, an impure emotion that is entirely ineffectual against the combined powers of the Magic Knights, who are doomed to succeed in carrying out their mission.

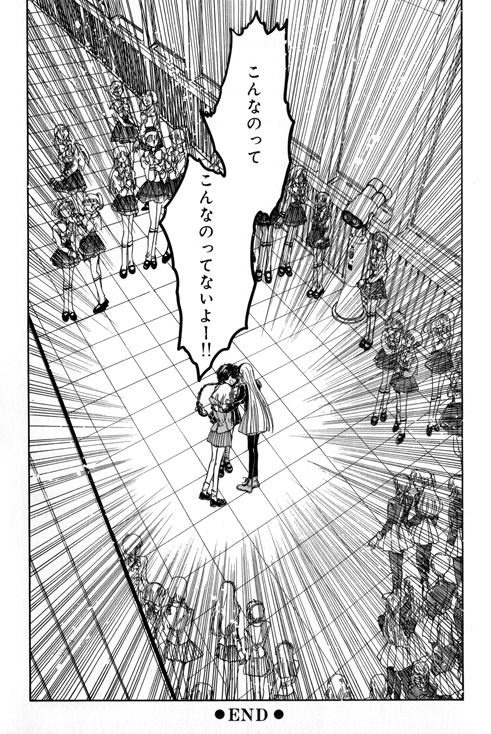

The demonic older woman is thus defeated by the pure-hearted shōjo, an outcome that was never in doubt. Based on the gendered character tropes and story patterns of shōjo manga and the various genres for boys that CLAMP’s manga emulates, this is simply how things work. In Magic Knight Rayearth, however, a happy ending is not forthcoming. Hikaru, Umi, and Fū are shocked by what they have done, and the manga ends abruptly with their realization. On the third-to-last page, Princess Emeraude dissolves into light, and, in the final two pages, the three Magic Knight are suddenly back in Tokyo, crying in each other’s’ arms. The manga closes with Hikaru screaming, “It can’t end like this!” – and yet it does end like this. Youth and innocence has defeated maturity and adult understanding, as per the conventions of shōjo romance and mahō shōjo fantasy, but no one is happy. In fact, this outcome is traumatic not just for the Magic Knights but also for the reader. By upsetting the reader, CLAMP also upsets the narrative cycle in which character tropes and story patterns are endlessly recycled. In its antagonistic and confrontational dynamic between virginal shōjo and sexually mature women, Magic Knight Rayearth mimics the shōjo romance and mahō shōjo fantasy that has come before it. However, by representing this character dynamic as tragic, CLAMP critiques the misogynistic tendency in anime and manga to villainize older women who possess both sexual maturity and political power.

Just as female fans of Sailor Moon are able to find messages of feminist empowerment in the series instead of polymorphously perverse possibilities for sexual titillation, female creators like CLAMP are able to stage feminist critiques of real-world sexual economies of desire within their application of gendered narrative tropes. Therefore, when cultural theorists such as Saitō Tamaki discuss otaku immersing themselves in fantasies that have nothing to do with the real world, they acknowledge shōjo series like Sailor Moon and Magic Knight Rayearth but completely fail to take into account the female viewers, readers, and creators for whom fictional female characters are not entirely removed from reality. Within the communities of women who consume and produce popular narratives, however, the female gaze is alive and well. This female gaze not only allows female readers to see celebrations of empowered female homosociality in works that would otherwise be dismissed as misogynistic (such as Sailor Moon) but also serves as a critical tool for female creators like CLAMP, who seek to overturn clichéd tropes and narrative patterns both as a means of telling stories that will appeal to an audience of women and as a means of feminist critique.

For more about CLAMP, please check out the CLAMP Manga Moveable Feast hosted by Manga Bookshelf.