Or, how to find dōjinshi in Tokyo. Here is what you need to know before you set out:

First, stores specializing in dōjinshi tend to fall into two categories, dansei-muke (for men) and josei-muke (for women). Dansei-muke dōjinshi are usually highly pornographic, and it is far from uncommon for them to feature the graphic rape of minors (or characters drawn to look like minors). The term josei-muke refers to the genre of boys love (BL), but the majority of the dōjinshi found in josei-muke stores aren’t BL at all but rather humor, parody, drama, or light heterosexual romance. You can usually tell what you’re getting from the cover, but every dōjinshi is enclosed in a plastic slipcase that you can’t (and shouldn’t try to) open until you actually buy the thing. Most general-audience dōjinshi are ¥210, and a good rule of thumb is that, the more expensive the dōjinshi, the more pornographic its content. There are exceptions to this – the dōjinshi in question may be particularly rare, or particularly good, or by a particularly well-known artist – but again, you can usually make an educated guess on the content based on the cover.

Second, you need to know how to read Japanese. It goes without saying that all dōjinshi are written in Japanese (regardless of whether English is used on the cover). More importantly, no English is used in any of the stores. Dōjinshi are organized in kana order by the title of whatever work they’re based on and grouped according to genre (ie, video games, shōnen manga, Western television shows, Korean boy bands, etc). Dōjinshi based on more popular series (such as Hetalia or Final Fantasy VII) are further organized by pairing or dōjin circle. You’re therefore going to need to be able to read Japanese in order to navigate the stores. The staff at these stores is generally happy to help you find what you’re looking for, but you need to tell them the title of the gensaku (original work on which the dōjinshi is based) in Japanese before they can help you. If you’re not confident about your Japanese, it might be useful to bring a friend to help you navigate and to visit the stores as soon as they open (so they won’t be crowded).

With that in mind, here we go!

Ikebukuro

Ikebukuro, and more specifically Otome Road, is the mecca for fujoshi. It should be the first and last place that any female dōjinshi hunter visits. If you’ve never been here before, let me promise you that it’s anything beyond your wildest dreams. Bring lots of money.

Ikebukuro Station is absolute chaos, and it’s very easy to get lost. In general, though, you want to head towards the Seibu side of the station. There are several exits out of the JR portions of the station; but, if you follow the yellow signs for “Sunshine” (which are referring to Sunshine City), you should be headed in the right direction. The specific exit you want to take out of the station is Exit 35.

You’ll emerge from chaos into chaos. There will be a huge Bic Camera to your left and an enormous throng of people directly in front of you. Follow the throng straight ahead and then to the left to a street crossing. On the other side of the street will be a Lotteria on the left and a Café Spazio on the right. Cross the street and pass in between these two restaurants to enter an enormous shopping street called Sunshine Plaza. Walk all the way down the street until you reach a highway overpass. Cross the road under the overpass on the right side and then turn right in front of the Toyota Auto Salon. Walk until you reach a Family Mart, and then take a hard left all the way around the corner building. You should see an Animate in front of you. Congratulations! You’ve reached Otome Road.

Otome Road begins at the Animate and ends at the three-story K-Books Dōjin-kan. This K-Books is probably the single best dōjinshi store in all of Tokyo. They have dōjinshi for every conceivable fandom, and they usually have the same dōjinshi for less money (¥210 as opposed to ¥420) than at the Mandarake you passed on the way. They also have tons of original dōjinshi and dōjinshi sets (all of the dōjinshi in a series, or a dōjinshi packaged with extras like fans or postcards). Keep in mind that all of the dōjinshi on the second floor are new and can usually be found for a fraction of the price on the third floor, where they sell used dōjinshi. What I like about this particular store is that they have a lot of general interest dōjinshi that have nothing to do with yaoi. The previously mentioned Mandarake has a much stronger focus on BL dōjinshi, and it’s a good place to find original dōjin artbooks as well.

There are two different branches of Café Swallowtail (a famous butler café) on Otome Road, one next to the Mandarake and one next to the K-Books. If you’d like to visit, make sure that you’re familiar with the process of attaining a reservation before you go. The two locations have two different reservation procedures, and you can only make a reservation for a thirty-minute time slot. Don’t be afraid of trying one out, even if your Japanese isn’t perfect, but it’s way more fun to go with a friend (especially since the cafés are geared towards parties of two).

On your way through Sunshine Plaza from the station to the highway overpass, you can turn right at any point to enter a maze of manga stores, maid cafés, and cat cafés. Also, if you’re really into Japanese youth culture and fashion, try entering Sunshine City (you’ll know it when you see it), which is the size of a small city – a small city filled with clothing and accessories for teenagers (and an aquarium). Finally, the cinemas lining Sunshine Plaza are the best places to go to see an animated movie, whether it’s the new Ghibli film or the latest feature-length spin-off of a popular franchise like K-ON. They’re also good places to pick up all the guidebooks and merchandise that accompany these movies. If you need to chill out and kill time before a show, you can always take advantage of one of the many many many kitschy love hotels (which are cheap and clean and more than likely have a nicer shower than your apartment or hotel) right off the main street.

Akihabara

Akihabara is where you go to get porn. The end.

Okay, seriously. Akihabara specializes in dansei-muke dōjinshi. There are tons of small dōjinshi stores located several floors up or several floors down from the narrow side streets that twist through the main electronics district. Many of these smaller stores cater to specific fetishes, and some of these fetishes might be extremely disturbing to some people. I will therefore leave the true exploration of this area to the truly adventurous. Thankfully, the Akihabara branches of K-Books and Mandarake are fairly mainstream (although still filled with porn).

Take the Akihabara Electric Town exit out of the JR station. Straight ahead you’ll be looking at several columns and a storefront, so head to your left to exit. Once outside the building, turn to your right. A few dozen feet down the left side of the street you’ll see the Radio Kaikan. There are several entrances into this building, but you want to take the escalator that goes directly from the storefront up to the second floor. (It’s right next to the display of electronic dictionaries. Incidentally, this is the single best place in Japan to get an electronic dictionary, as it has all the latest models at 40-60% off the list price.) Once off the escalator, go up the stairs to the third floor and then turn to your right to enter the K-Books dōjinshi store. Whatever fandom you’re interested in, from Evangelion to Azumanga Daioh, they have porn of it. They also have tons of fresh dōjinshi from the latest comic markets at reasonable prices, as well as other dōjin goods such as Vocaloid albums and body pillow covers.

[ETA: As of July 1, 2011, the Akihabara branch of K-Books has relocated to the “Akiba Cultures Zone” (AKIBAカルチャーズZONE). To get there, use the directions for Mandarake but turn to your left before the Sumitomo Fudōsan instead of after it. In other words, turn left at the Daikokuya electronics store (you should see the K-Books storefront reflected in the glass windows of the Sumitomo building). The first floor houses used manga, and the dōjinshi are on the second floor.]

The other big dōjinshi store in Akihabara is the Mandarake complex, which has separate floors for dansei-muke dōjinshi and josei-muke dōjinshi (as well as other floors for other things, like used manga and cosplay supplies). To get there, go straight past the Radio Kaikan until you reach a large street. This road is Chūō-dōri. Cross over to the other side of the street and turn to your right. Walk for about two blocks until you read the Sumitomo Fudōsan Building. Turn to your left after this building onto a small street, and you should see the Mandarake complex ahead on the right. The fourth floor has josei-muke dōjinshi, and the third floor had dansei-muke dōjinshi. The selection on both floors isn’t the best, but you can sometimes find stuff here that you can’t find anywhere else, such as the dōjinshi of a popular circle called CRIMSON, which publishes print versions of its dōjin visual novel games.

On the way to Mandarake, you will have seen the main branch of Tora no Ana on the other side of Shōwa-dōri. Tora no Ana publishes its own art books and dōjinshi (and a few mainstream manga like Fuku-Yomo), but its third floor is a fujoshi paradise of BL manga, manga magazines, and dōjinshi. Even if you’re not into porn, it’s worth visiting the Tora no Ana in Akihabara just to check out the culture.

Shibuya

The main attraction of Shibuya is the Mandarake, which specializes in used pornographic manga and figurines but has a sizeable josei-muke dōjinshi section with a unique selection. Since this Mandarake is somewhat removed from Otome Road, the dōjinshi in stock here aren’t the newest or the freshest that you can get your hands on, but this can work to your advantage if you’re looking for dōjinshi based on older titles like Sailor Moon, Revolutionary Girl Utena, Nodame Cantible, Hellsing, Wild Arms, Final Fantasy IV, or the next-to-latest incarnation of the Pokémon franchise. Also, if you’re looking for dōjinshi based on manga by CLAMP or the films of Studio Ghibli, this is the place to go. If you’re looking for original dōjinshi drawn by an artist like Ono Natsume or Yoshinaga Fumi, this is also the place to go. This particular store also has the friendliest and most helpful staff I’ve yet encountered.

To get there, take the Hachikō exit out of the JR station and orient yourself so that you’re facing the Tsutaya building with the Starbucks café. Head down the left side of the big road passing to the right of this building (the 109 Men building will be on the other side of the road). In about a block the Seibu department store will be on your left. Turn left to pass in between the two Seibu buildings (there will be bridges above you). Go straight on that street until it splits at a kōban (police box) and take the right fork. The Mandarake will be a block down on the left side of the street, directly across from a Choco Cro café. You’ll need to go down several flights of stairs to reach the actual store. (For the record, there is another entrance into the store, but this is the one that leads directly to its dōjinshi section.)

While we’re on the topic of Shibuya, I should also mention the Tsutaya I referred to in the directions. In my opinion, this particular branch of the chain is the single best place to buy new manga in Japan. They have multiple copies of all the volumes of all of the latest manga in stock, and they have really cute displays created by the staff to highlight interesting and notable titles. This is the place to go to find out what is popular in Japan right now, and you can take to elevator down to the basement to do the same trick with video games before progressively working your way up through music, movies, and literature.

If you find yourself spending a lot of money, go ahead and apply for a T-Point card, which also works at Book-Off (and Family Mart convenience stores and Excelsior coffee shops, for what it’s worth). Book-Off is a chain of used book stores known for its ridiculously low prices and the excellent condition of its used merchandise. In essence, after using your point card for the first two or three volumes of a manga at Tsutaya, you can get enough points to get a used copy of the next volume for free at Book-Off. And speaking of Book-Off, the one across the street from the Shibuya Tokyu Hands is a manga lover’s paradise. They also have tons of used light novels, art books, and video game strategy guides that you won’t even find in Akihabara.

Nakano

Nakano is a bustling, working-class shopping area a few stops out of the Yamanote loop on the JR Chuo line. The area is a bit out of the way of just about everything, but it’s home to Nakano Broadway, a rundown warren of manga stores and hobby shops. The top three stories of this indoor shopping complex are a hive of Mandarakes. If you have any sort of hobby related to anime or manga or video games, whether it’s cel collecting (fourth floor), cosplay (third floor), or researching Taishō-era children’s magazines (second floor), Nakano Broadway is where you go to spend all of your money. There are also tiny stores specializing in Ninja Turtles action figures from the nineties, old Japanese coins, and prayer beads and power crystals. There is even a Mandarake store called Hen-ya that, as its name implies, is a treasure hoard of the weird, baffling arcana of postwar Japanese pop culture.

From the JR Nakano station, take the north exit for Sun Plaza. Head around to your right past the turnstiles to exit the station, where you’ll see an open-air bus station in front of you. Beyond the bus station and to the right is the entrance to a shopping arcade called the Nakano Sun Mall, which is marked by yellow arches. Enter the shopping arcade and walk straight back all the way to the end to reach Nakano Broadway.

There’s nothing to see on the first floor, but you can take the escalator up to the third floor to reach the most awesome used manga store ever (run by Mandarake, of course). Whether you’re looking for editions of manga like Rose of Versailles from the eighties or the whole back catalog of a manga magazine like Monthly Cheese, they’ve more than likely got it stashed away somewhere. If you want to go straight to the dōjinshi stores, skip the escalator and take the stairs to the right of the escalator up to the second floor. Turn left from the stairs and then left again around the corner, and you should reach a dansei-muke store and a josei-muke store right across from each other a bit down the corridor.

Since Nakano is so out of the way, and since Mandarake keeps a lot of its excess stock up on the fourth floor, you can find old dōjinshi at these stores that have disappeared from just about everywhere else (such as those based on Harry Potter). The josei-muke store in particular specializes in anthologies, and you can strike real gold here if you don’t mind paying significantly more than the usual ¥210 – dōjinshi anthologies are huge and beautiful but can cost up to ¥5,000 (although ¥1,050 is more common). It takes a bit of work to get out to Nakano, and you’ll probably get seriously lost in Nakano Broadway, but it’s definitely worth the trip for a true treasure hunter.

***

All of the directions I have given take it for granted that you’re using one of the JR lines (such as the Yamanote-sen). Be aware that these directions may not apply if you’re using one of the Tokyo Metro lines (or another private line like the Keio-sen).

K-Books, Tora no Ana, and Animate all have point cards. These cards are free and allow you to accumulate points with each purchase. You can use these points to either take a discount off future purchases or to get limited edition goods that can only be bought with points. If you’re going to be spending a long time in Japan or are planning on spending a lot of money during a short visit, it might be worth your while to ask for one of these cards. (In the case of K-Books, you might want to just get one anyway, since they give you a choice of really cute, collectible cards.) You can just ask your cashier for a card at K-Books and Tora no Ana, but you’ll need to fill out an application form with your address in Japan at Animate.

All of the stores I have mentioned by name accept Visa and Mastercard. The only caveat about using a credit or debit card is that you may not be able to get points on your point card for that purchase. The policy on accumulating points for credit purchases differs from store to store (especially in Akihabara), but you shouldn’t have a problem anywhere in Ikebukuro.

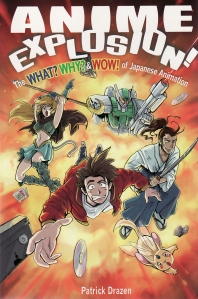

Finally, if this guide has made you giddy with excitement, please consider investing in the book Cruising the Anime City. It’s a bit dated (just as this guide is probably going to be in a year or two), and it betrays a strong masculine bias, but it’s still awesome.