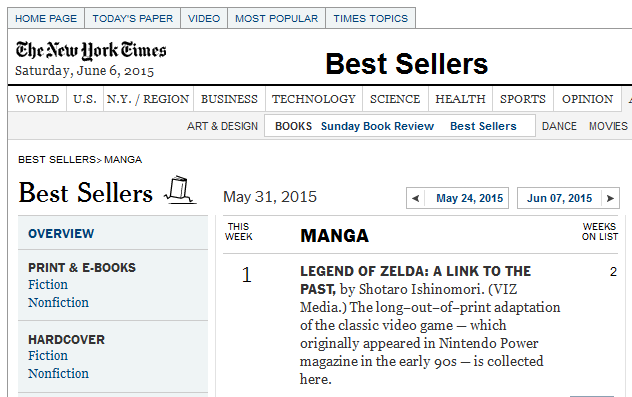

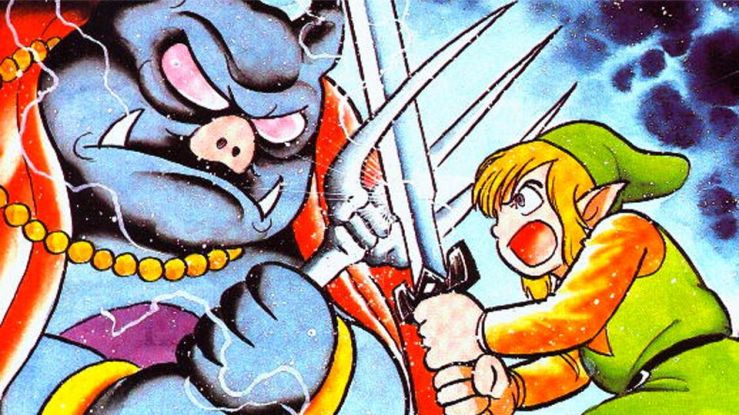

On January 18 of 2015, Ed Chavez, the Marketing Director at manga publisher Vertical, replied to a Twitter user’s question on ask.fm regarding whether manga is becoming a niche entertainment industry outside of Japan. Chavez’s response was a definite “maybe.” After stating that shōnen manga is selling just as well – if not better – than it always has, Chavez added the caveat that, “Unlike the 00’s, where a shojo boom introduced a whole new demographic to manga, there hasn’t been a culture shifting movement recently.” Johanna Draper Carlson, one of the most well-respected and prolific manga critics writing in English, responded to Chavez’s assessment on her blog Comics Worth Reading. She agreed with him, adding, “I find myself working harder to find series I want to follow. Many new releases seem to fall into pre-existing categories that have already demonstrated success: vampire romance, harem fantasy, adventure quests, and so on. It’s harder to find the kind of female-oriented story that [has always appealed] to me.” Meanwhile, the manga that stood at the top of the New York Times’s “Best Sellers” list for manga that week was the seventh volume of a series called Finder, a boys’ love story targeted at an over-18 female audience.

What we’re seeing here, from Chavez’s reference to a former boom in shōjo manga sales to evidence that even a title from a niche category for women can sell just as well as the latest volume of the shōnen juggernaut One Piece, is that girls and women in North America do care about manga, and that they are active participants in manga fandom cultures. What I’d like to do today is to provide a bit of background on how female readers were courted by manga publishers – specifically Tokyopop – and then to demonstrate how manga has influenced the women who grew up with it to reshape North American comics and animation with a shōjo flair.

I’d like to argue that, despite periods of relatively low sales in the United States, shōjo manga (and the animated adaptations of these manga) have had a strong cultural impact on recent generations of fans. During the past fifteen years, fan discussions and fannish artistic production have nourished diverse interests in Japanese cultural products, which are in turn beginning to exert a stronger influence on mainstream geek media. Using M. Alice LeGrow‘s graphic novel series Bizenghast and Natasha Allegri‘s animated webseries Bee and PuppyCat as case studies, I want to demonstrate how it is not only the visual styles and narrative tropes of shōjo manga that have increasingly begun to influence North American media, but the creative consumption patterns of shōjo fandom communities as well.

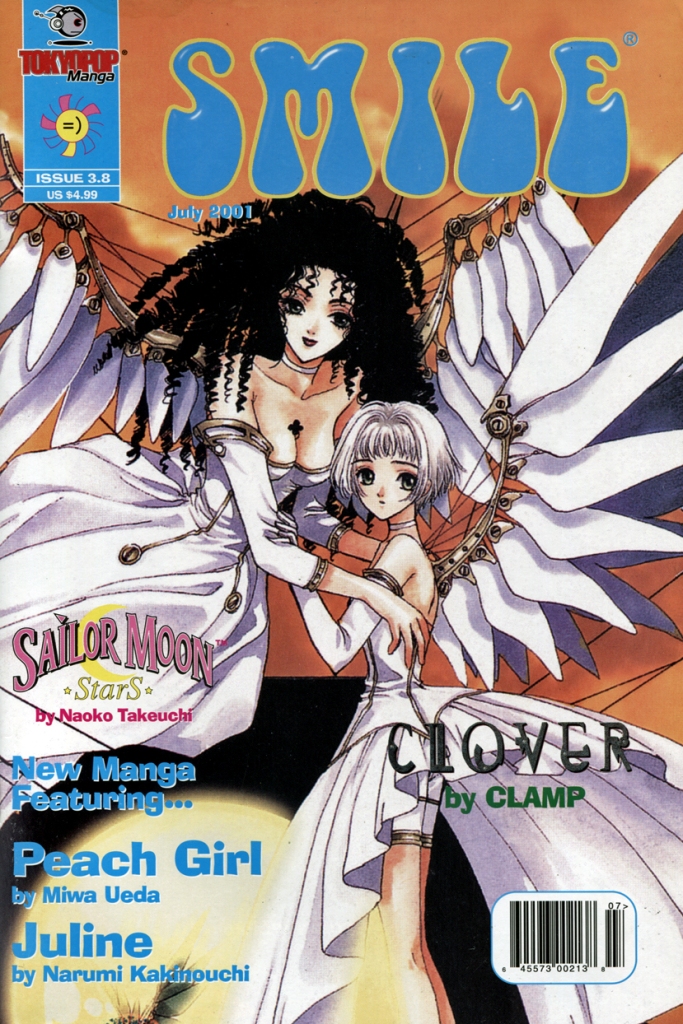

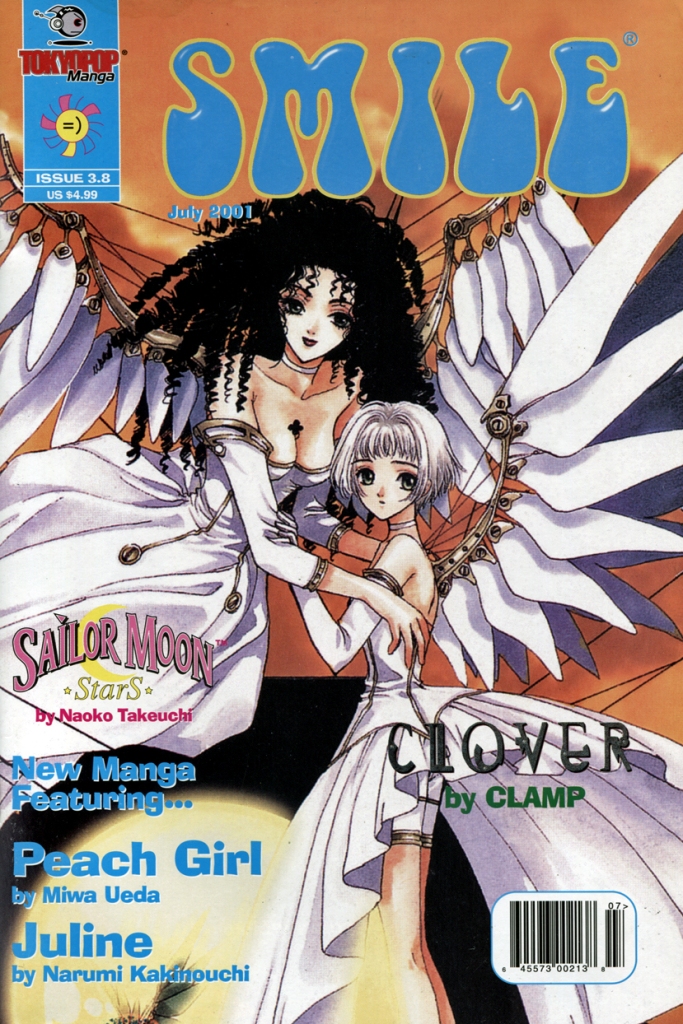

Before I talk about American interpretations of shōjo cultures, however, I’d like to skim through a bit of publishing history. In the mid-1990s, there was a Barnes-and-Noble-style big suburban box store called Media Play, which had an entire section devoted to manga and Japanese culture magazines. One of the most prominent of these magazines was fledgling publisher Tokyopop’s manga anthology MixxZine, which began serialization in 1997 and ran the manga version of Sailor Moon as well as the similarly themed fantasy shōjo series Magic Knight Rayearth and Card Captor Sakura. In 1999, the magazine changed its name to “Tokyopop” and began to target an older male audience by dropping its shōjo manga and focusing on shōnen and seinen titles. Tokyopop the magazine folded in 2000 but was survived by a publication called Smile, which was a bulky, 160-page monthly magazine that serialized only shōjo manga. In 2001, Media Play’s parent company was bought out by Best Buy. When Media Play stores were closed, Tokyopop lost a major venue for its magazines, and Smile folded in 2002.

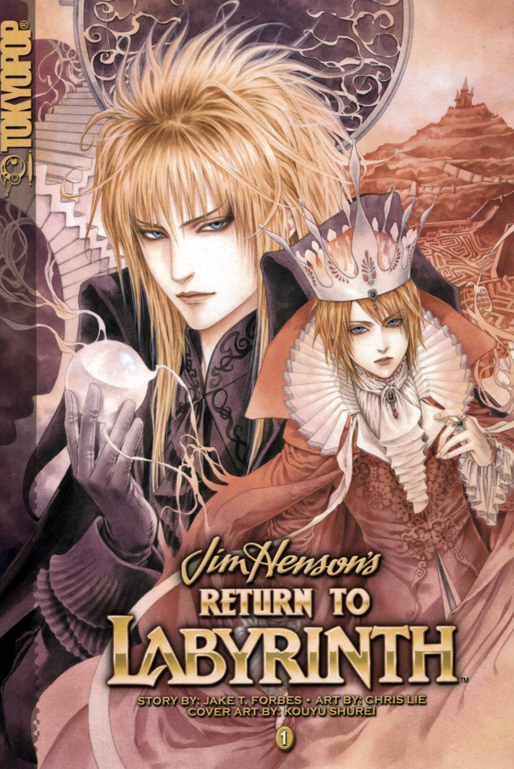

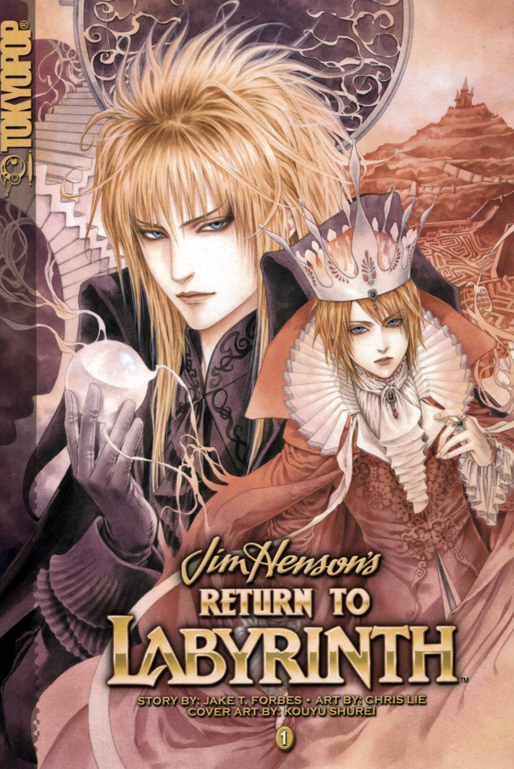

Now that a large fanbase had been created, however, Tokyopop was able to launch a program it called “Global Manga,” which was kicked off by the 2002 “Rising Stars of Manga” talent competition. The winning entries were published in a volume of the same size and length of the publisher’s Japanese manga titles. There were eventually eight volumes of The Rising Stars of Manga, with the last appearing in the summer of 2008. During this time, certain winners were encouraged to submit proposals to Tokyopop, which published their work as OEL, or “original English language,” manga. By my count, about half of Tokyopop’s OEL manga were shōjo series. Examples include Peach Fuzz, Shutter Box, Fool’s Gold, and Sorcerers & Secretaries. Tokyopop promoted these titles with free “sampler” publications distributed by mail and at anime conventions, which were exploding in number and attendance in the United States and Canada during the 2000s. Although users of anime-related message boards and fannish social media sites debated the company’s use of the term “manga” to describe these graphic novels, Tokyopop was able to attract well-known American entertainment franchises to the medium, such as Star Trek, Battlestar Galactica, World of Warcraft, and for the girls, Jim Henson’s Labyrinth, featuring David Bowie’s Goblin King in all his spandex-clad glory.

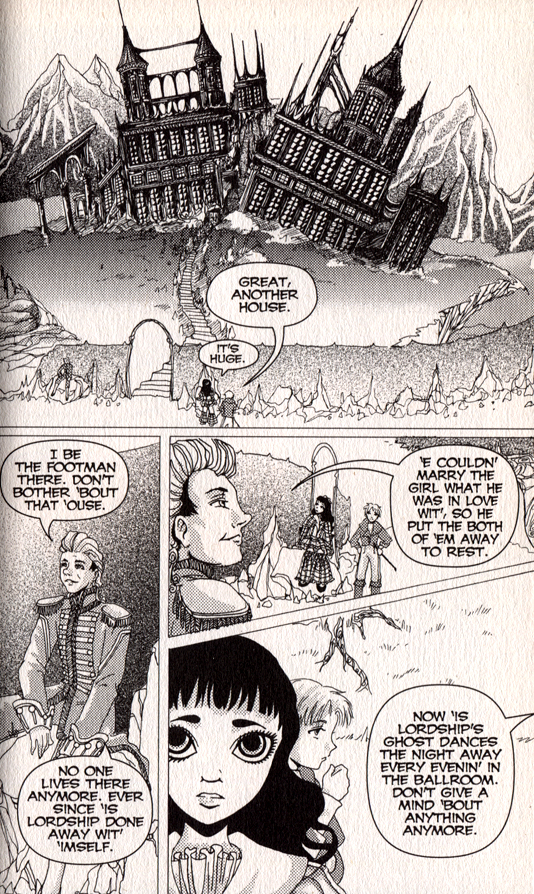

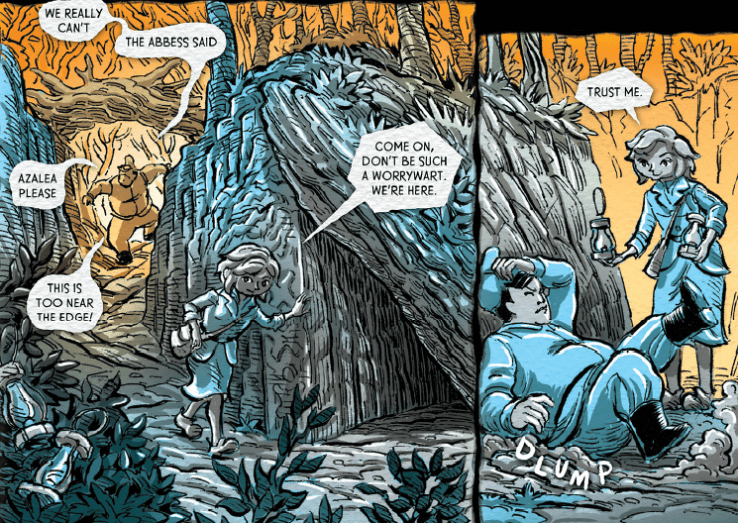

One of the Tokyopop’s most popular OEL manga titles was M. Alice LeGrow’s eight-volume series Bizenghast, which, like Sailor Moon and Cardcaptor Sakura, is a shōjo story with shōnen elements. LeGrow’s story takes the adorable mascot creatures, monsters-of-the-week, cute costumes, adoring and beautiful young men, and powerful female villains of Japanese manga for girls and transplants them to the small Massachusetts community of Bizenghast, which becomes an Edgar Allan Poe-ified Gothic wonderland after dark. The art style combines the huge eyes and wide panels of fan-favorite shōjo manga like Fruits Basket and Fushigi Yûgi with steampunk Art Deco motifs and Edward Gorey-style line etchings. The artistic and narrative conventions of manga and the stylizations of Western fantasy are so delicately blended and intermixed that it’s impossible to tell whether Bizenghast is a manga with American influences or a graphic novel with Japanese influences.

What I want to highlight is the way that the Tokyopop publications of each volume in the Bizenghast series included a section at the end for fan art and cosplay photos, thus encouraging and legitimizing reader participation in the way that shōjo magazines have done since the early twentieth century in Japan.

Instead of eschewing or actively opposing fandom involvement, and specifically female fandom involvement, Tokyopop pursued it, allowing LeGrow to maintain her presence on the fannish artistic networking site deviantART, where she was able to interact with her fans. Due to the non-localized nature of the internet, LeGrow was able to build a fanbase that stretched around the globe, with Bizenghast being published in translation in Germany, Finland, Russia, and Hungary, as well as in several countries of the British Commonwealth, including Australia and New Zealand. In addition to assigning Bizenghast its own dedicated website, Tokyopop released a light novel adaptation, an art book, and even a coloring book based on the world of the manga. Although Tokyopop shut down its publishing operations in May 2011, it continued to offer certain titles through a print-on-demand service managed by the online anime retailer The Right Stuf. The initial line-up of these titles included the massively popular manga Hetalia Axis Powers and the eighth and concluding volume of Bizenghast. What I’d like to emphasize here is that, in its publication and promotion of Bizenghast as an OEL shōjo manga product, Tokyopop actively promoted the sort of interactive fan consumption utilized by Japanese shōjo manga publishers – and this encouragement paid off, quite literally.

Multiple market watchers have located the peak of United States manga sales in the mid-to-late 2000s. Even though Tokyopop ceased its manga magazines earlier in the decade, Viz Media stepped in with an English-language version of Shonen Jump, which was paired with a monthly sister magazine, Shojo Beat. Shojo Beat, which ran from June 2005 until July 2009, also styled itself as a lifestyle magazine, running articles about clothing, makeup, and real-life romantic concerns. Although Shojo Beat did not include OEL manga, manga publisher Yen Press’s publication Yen Plus did. From its launch in July 2008, the editors of Yen Plus solicited reader contributions, which resulted in both one-shot and continuing OEL manga appearing within the pages of the magazine.

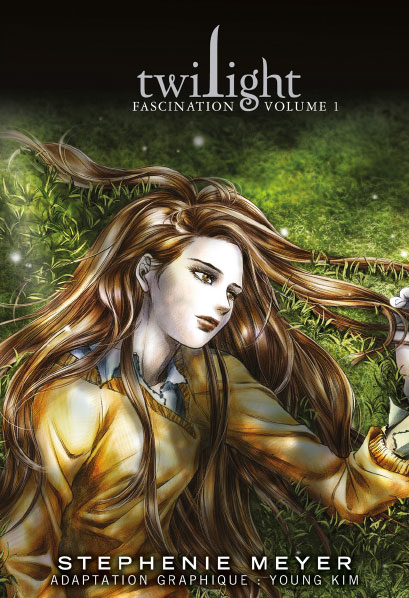

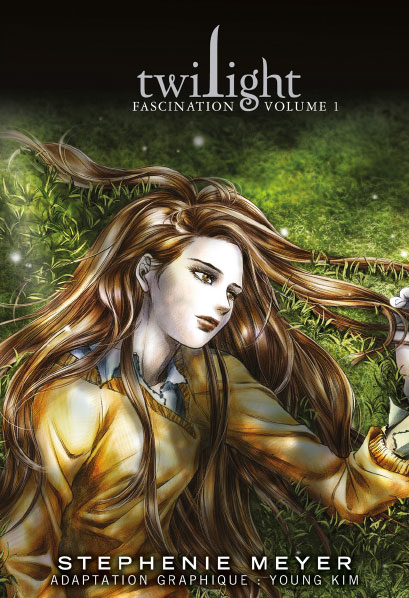

In addition, Yen Press’s parent company Hachette began releasing manga adaptations of some of its biggest young adult properties, including Gossip Girl, Gail Carriger’s The Parasol Protectorate series, and, of course, Twilight. For our purposes, it’s interesting to note that these manga adaptations all had a strong shōjo feel, as did other franchise manga revisionings created by longstanding American comics publishers such as Marvel and Vertigo. What these publishers seemed to be jumping on was the idea that manga could reach an audience of young women (and young-at-heart women) who may have felt excluded from traditionally male-centered genres like action comics and science fiction. These female readers increasingly came equipped with access to online and in-person fandom networks, which could help ensure the longevity and profitability of any given franchise, as was famously the case with Star Trek and Harry Potter.

What we’re seeing, then, is the creation and growth of an audience for shōjo manga that began in the 1990s and has extended throughout the past two decades. So – has this changed anything? I’d like to argue that it has, and that we’re starting to see a definite shōjo influence on mainstream entertainment media in North America.

One of the most interesting incarnations of this trend is Cartoon Network’s animated television series Adventure Time, whose producers have actively scouted young talent from places like comic conventions and fannish art sharing websites such as Tumblr. A number of these artists are women from the generation that grew up reading and watching shōjo series such as Sailor Moon and Revolutionary Girl Utena, and easily identifiable references to these titles occasionally pop up in the show. Rebecca Sugar, a storyboard artist for Adventure Time, ended up being given a green light by Cartoon Network to create a magical boy show, Steven Universe, that features all manner of references to anime, manga, and video game culture. Natasha Allegri, another storyboard writer and character designer for Adventure Time, launched a Kickstarter project backed by Adventure Time‘s Studio Frederator for a magical girl animated series called Bee and PuppyCat, which received an overwhelming amount of support from both Adventure Time fans and the enormous shōjo manga fanbase on Tumblr.

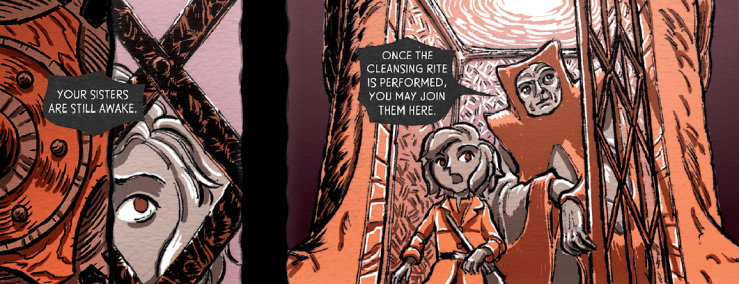

What’s really cool about these three properties is that they all have separate monthly comic book incarnations published by Boom! Studios. There’s a lot to be said about these comic books, but what I want to emphasize here is that each monthly issue features shorts and variant covers by young and upcoming artists. The comic book version of Bee and PuppyCat is especially notable in that most of its contributing artists are female, and many of them include obvious stylistic and topical references to elements of Japanese popular culture such as Studio Ghibli character stylizations, magical girl henshin transformation sequences, and role-playing video games. Although Natasha Allegri has stated in multiple interviews (here’s one) that she’s a fan of manga such as Sailor Moon and Takahashi Rumiko’s supernatural romance InuYasha, and even though the influence of these titles is quite clear in her work, Bee and PuppyCat has not been promoted as a type of OEL anime but rather as just another cool new addition to the Studio Frederator lineup. In other words, the strong shōjo elements of the show and its comic book are presented as completely natural and naturalized to a North American audience.

I’m going to wrap things up by summarizing my main points. First, I think we can say that the iconography of shōjo manga and anime are entering American popular culture full force. Second, I believe that seeing better representation of diverse female characters in shōjo manga has encouraged more young women outside of Japan to seek careers in comics and animation. Third, although it’s difficult to make strong statements in the current market, I think it’s safe to say that the “reader participation” model employed by Japanese shōjo publishers has been fairly financially successful in the United States. Fourth and finally, I’m going to conclude that we will therefore see an even stronger embrace of shōjo-related narrative influences, art styles, and fandom cultures as the members of the Adventure Time and Bee and PuppyCat generation, who are currently in college, start coming out with their own work. It’s an exciting time to be a fan of shōjo manga, and I’m happy that young women and men are still as excited about shōjo-flavored comics and animation as I was when I first discovered Sailor Moon almost twenty years ago.

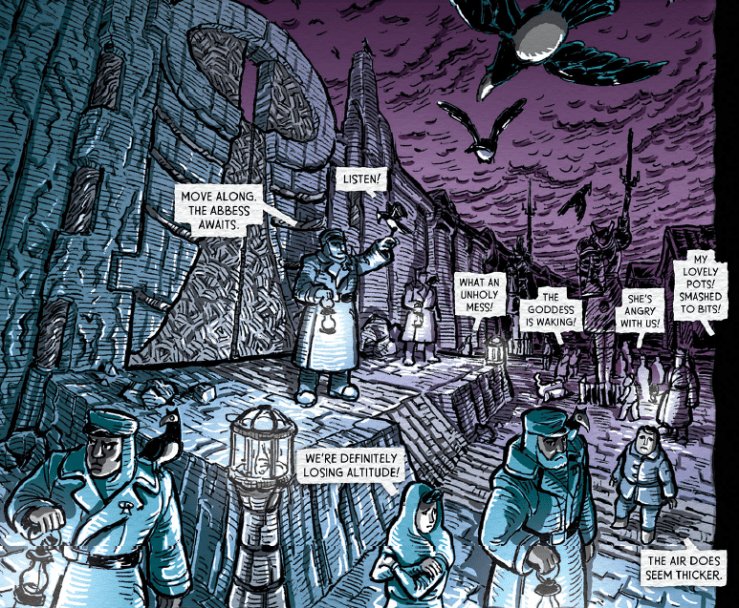

The above image is a scan of a page from Meredith McClaren‘s short comic in the sixth issue of the Bee and PuppyCat comic book series.