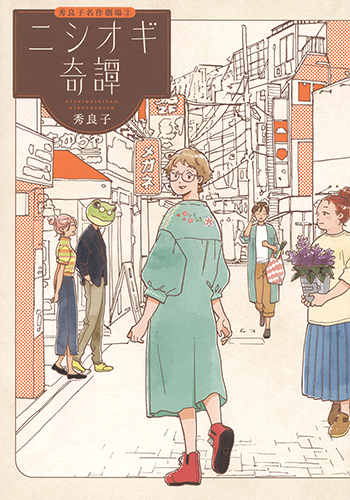

Nishi Ogikubo is a stop on the JR Chuo Line that runs through central Tokyo and out into the western suburbs. The neighborhood, known as “Nishiogi” to its residents, is right next door to Kichijōji, a trendy area filled with small restaurants, cafés, antique stores, art galleries, and beautiful green parks. Like Kichijōji, Nishiogi has an artsy and laid-back vibe…

…but it doesn’t exist. Not officially, anyway. So how do you get there? According to anonymous forum posts, if you take the Chuo local train that stops at every station, every so often it will stop at Nishi Ogikubo. If you choose to get off at the station that doesn’t exist, however, perhaps you shouldn’t be surprised by the people you encounter there!

Hideyoshico’s 2025 manga Nishiogi Kitan (Strange Tales of Nishiogi) collects seven stories about a fictional neighborhood where anything can happen. Despite the oddness of some of the residents, Nishiogi is chill and pleasant, and the neighborhood is a lovely place to spend time.

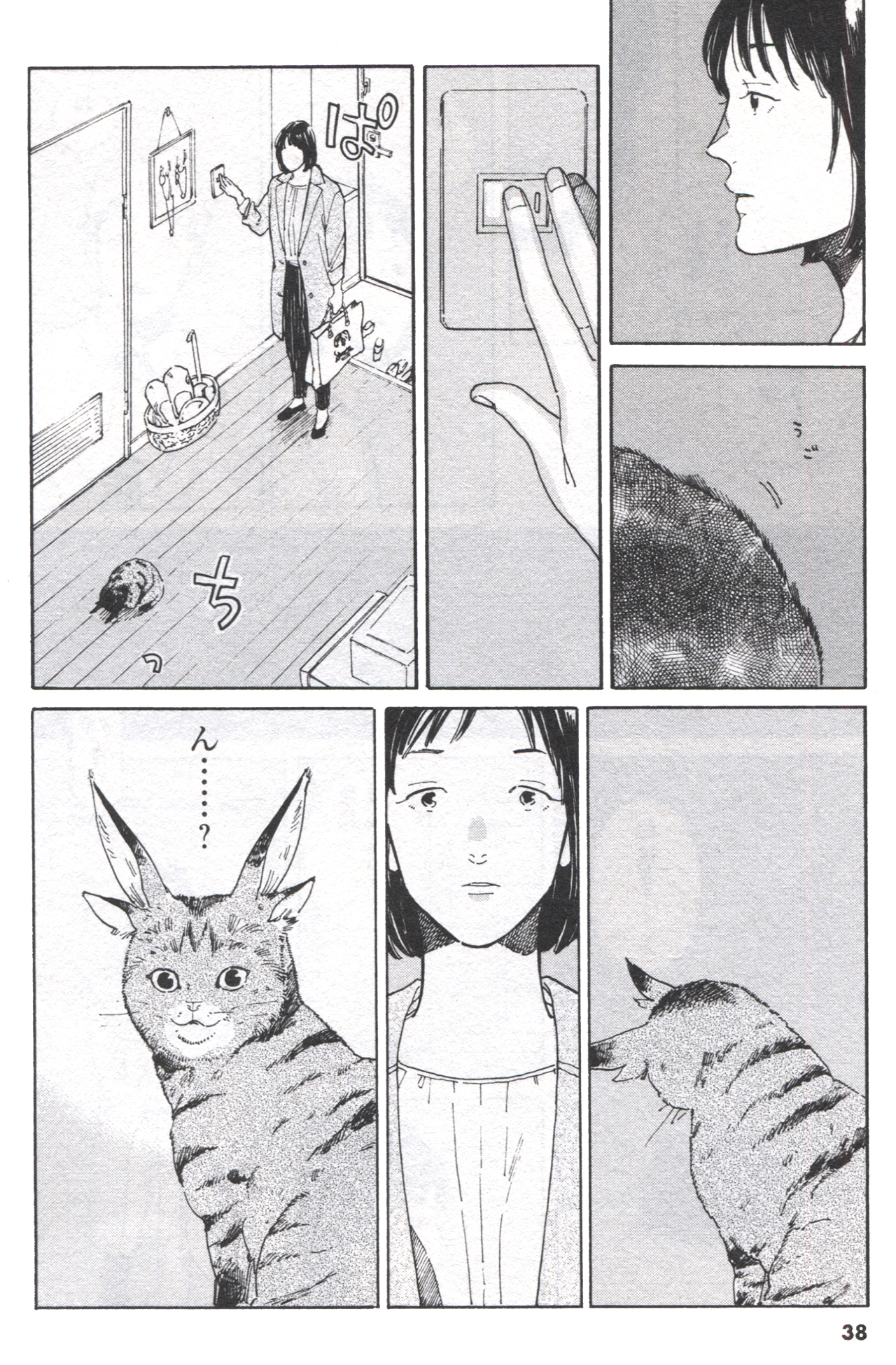

The second story in the collection, Mayonaka no hōmonsha (Late-night Visitor), is a great introduction to everyday life in Nishiogi. While walking home one night, an office worker named Kurata realizes that a cat is following her. It’s not like any cat she’s ever seen, but it seems to have taken a shine to her. She brings the cat home and names it Ohagi. Ohagi’s appearance changes every day, but the most noticeable shifts occur when Kurata is forced to stay late at the office.

When Kurata returns especially late one night, she finds her potted plant overturned and all sorts of leaves scattered across the floor. Hiding under her bedcovers is a big fat tanuki.

Kurata realizes that Ohagi has been exhausting itself while trying too hard to be something it’s not, and this causes her to realize that she’s more than a little tired herself. The next time her boss asks her to work late, she politely tells him that she has a pet at home to take care of, and that he can do the work himself. When given more love and attention, Ohagi becomes a little better at taking the shape of a cat… sort of.

Back in the day, Hideyoshico used to draw dōjinshi fancomics based on Yotsuba&!, and there are hints of the same themes in the collection’s fourth story, Natsu no ie (Summer House). While walking the family dog one afternoon, a young boy passes an abandoned house rumored to be haunted. As the dog frolics in the overgrown yard, an unkempt man eats instant noodles on the porch. Though the man claims to be a ghost, the boy doesn’t believe him, and the two become friends. The reader can never be entirely sure if the man isn’t in fact a ghost, but this is a very sweet and charming story.

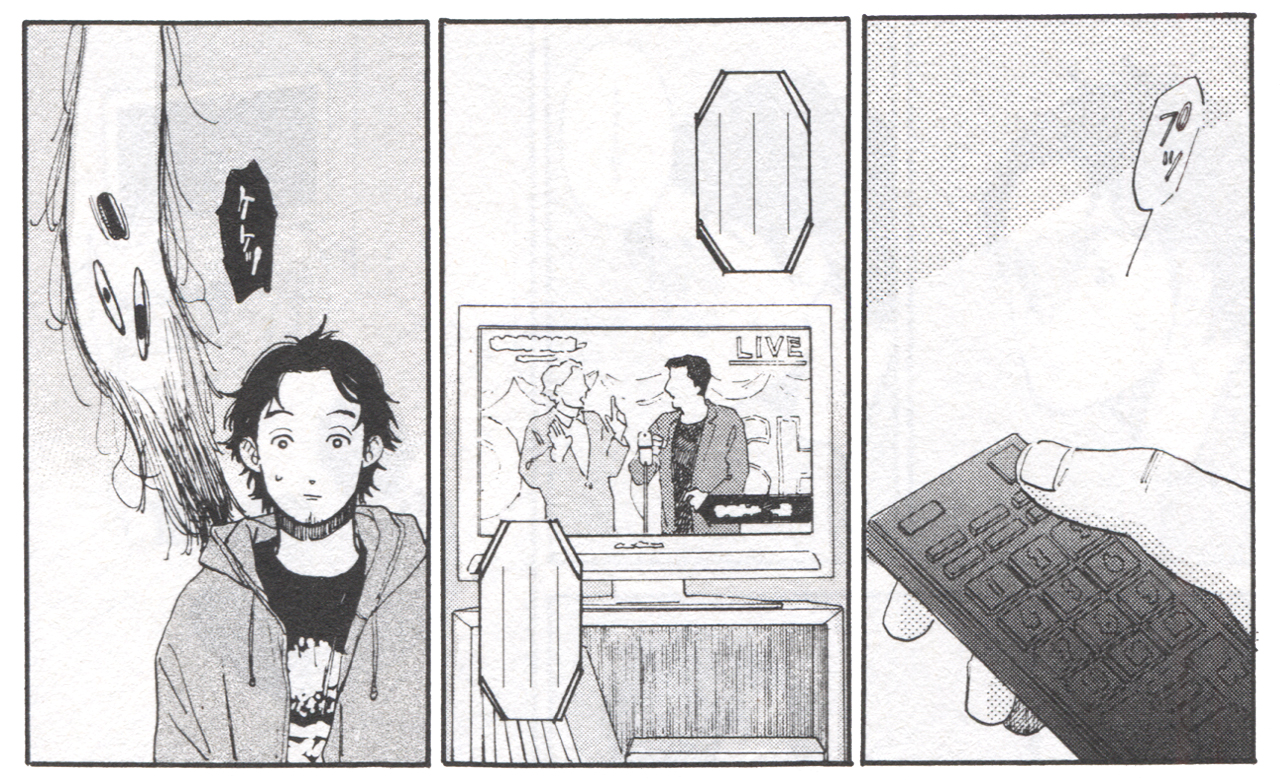

Because I love urban legends about cursed apartments in Tokyo, I’m a big fan of the story “New Heights Nishiogi Apt. 202,” in which a young musician befriends a horrorterror straight out of a Junji Ito manga. The man’s apartment may be haunted, but the rent is cheap, and the eldritch entity is a companionable and considerate flatmate, all things considered. This story isn’t about the man learning to accept his flatmate’s “difference,” as he doesn’t seem to mind that at all, but rather about him learning to respect the spirit’s feelings and boundaries despite his difficulties understanding someone who can’t communicate in human language.

Hideyoshico is a veteran BL manga artist, and traces of the standard mid-2010s BL illustration style occasionally surface in Nishiogi Kitan. All of the adult male characters are attractive, and I’m not complaining. There’s a wider visual range in the female characters, who seem a bit more grounded in reality, and I’m also impressed by how the artist has portrayed the cluttered interiors and alleyways of West Tokyo. Some of the background architecture is traced (which is 100% valid), but most of the ambience is hand-drawn and lovely to see on the page.

Each story in Nishiogi Kitan is perfectly paced according to a four-part narrative structure, which makes the collection easily approachable despite its array of out-of-the-ordinary scenarios. Though not saccharine by any means, Hideyoshico’s tone is unflaggingly good-natured, and the good humor of the characters is contagious. Though the themes of the stories in Nishiogi Kitan don’t shy away from darkness and nuance, the collection is a weird but warm ray of sunshine.