Onibi: Diary of a Yokai Ghost Hunter

Artists: Atelier Sentō (Cécile Brun and Olivier Pichard)

Translator: Marie Velde

Publication Year: 2016 (France); 2018 (United States)

Publisher: Tuttle

Pages: 128

This story was inspired by one of our trips to Niigata, during the fall of 2014. We dedicate it to the people we’ve met there. They welcomed us with overwhelming generosity and helped us discover the region and its secrets. Some of these people will appear in this book. We hope they will enjoy it.

This paragraph prefaces Onibi, a diary-style graphic novel written and drawn by Cécile Brun and Olivier Pichard, who work together as a creative team called Atelier Sentō. In the late summer and fall of 2014, Brun and Pichard were able to spend ten weeks living in the small village of Saruwada thanks to the efforts of Kosuke and Sumie Baba, who run a small restaurant and international guesthouse called Margutta 51. At the beginning of their stay, Brun and Pichard bought a toy Polaroid camera from a man who assured them that it could photograph spirits, so they went out ghosthunting. Onibi is the result of their travels and conversations.

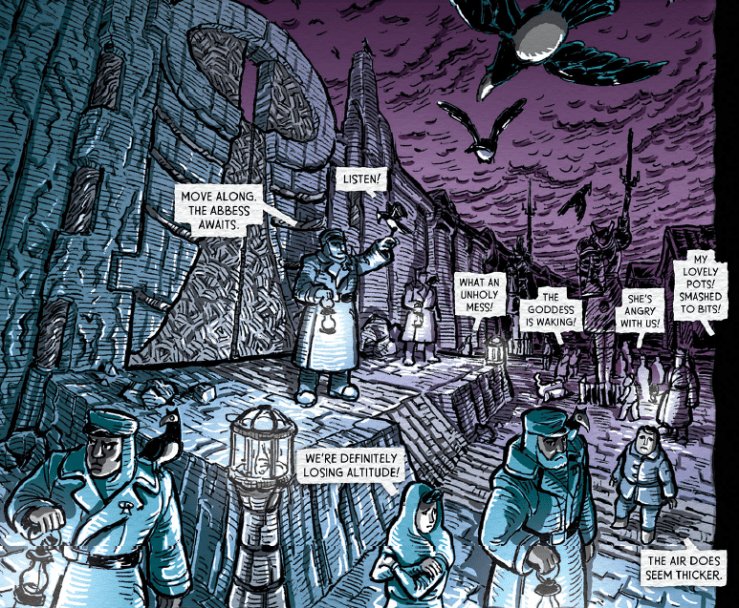

Along with a short prologue and epilogue, Onibi has seven chapters, each of which chronicles a local legend related to the yōkai of Niigata prefecture in northern Japan. A few of Brun and Pichard’s excursions were facilitated by the proprietors of Margutta 51, who introduced them to people with stories to share. Some of their encounters happened completely by chance, however, and most don’t play out as expected. In the second chapter, for example, Brun and Pichard take the train to a small village to find a creature called “Buru Buru-kun,” but they find that the old forest where it’s said to live has been cut down to make room for rice fields. In the seventh chapter, Brun and Pichard visit Osorezan, a temple located in the caldera of an active volcano where the world of the living and the world of the dead are believed to meet. They misplace their ghost camera as they explore the strange landscape surrounding the temple, but the conversations they have with their fellow pilgrims make the journey worthwhile.

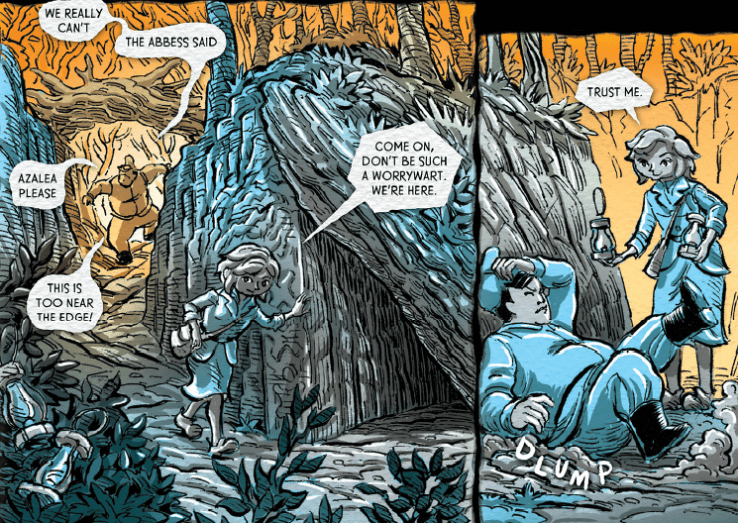

I especially enjoyed the fourth chapter, “Mountain’s Shadow,” which is about the pair’s chance encounter with a man who gives them a walking tour of Yahiko. The village is famous for its fall foliage, but it’s deserted during the week. After taking in the sights, Brun and Pichard step into a small udon restaurant, where they’re approached by a man who offers to tell them about the local yōkai. He takes them to a large tree in town and then up a hill to a mountainside temple, after which they embark on a hiking trail through the woods. Instead of taking the tram down the mountain once it gets dark, they decide to walk, and they hear strange noises in the trees as they descend. This episode is enhanced by its visual appeal as the color palette shifts from the brown of the restaurant interior to the gold of the afternoon sunlight in the village to the blue of the forest twilight.

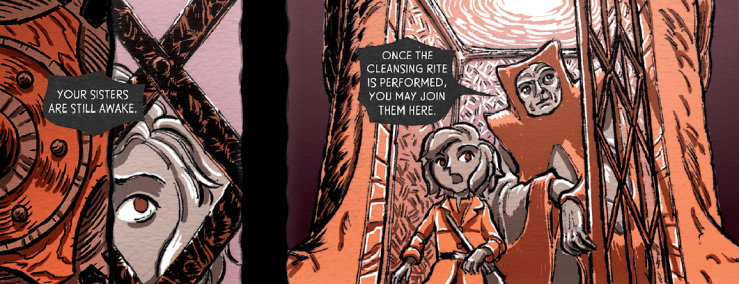

The comic artwork in Onibi is gentle and warm, with a gorgeous color palette and a pleasing compositional balance on each page. The humans who appear in the book are distinctive without coming off as caricatures, and the landscapes, townscapes, and interiors are striking. Brun and Pichard devote special attention to natural and artificial lighting and weather conditions, making the reader feel almost as if they’re walking right alongside the artists as the summer shifts into fall. Tuttle has released a beautiful Kindle edition of the book, but I highly recommend the print version, which allows the reader to appreciate the details and textures of the artwork.

Although it hints at some fairly dark themes, Onibi is more atmospheric than spooky, and it should be suitable for people of all ages. If I were teaching a class about Japanese folklore (and Onibi makes me dearly want to teach such a class), I think the graphic novel might serve as an interesting companion to Marilyn Ivy’s Discourses of the Vanishing, especially its chapter on Osorezan. Even for people with no background knowledge of Japan, Onibi is a fascinating exploration of a beautiful part of the world, as well as a lovely introduction to the people who live there – and the supernatural creatures who might just coexist with them.