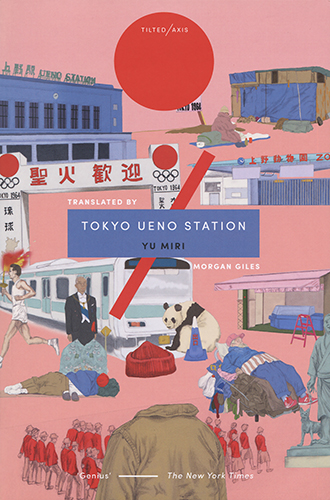

Yū Miri’s 2014 novel Tokyo Ueno Station is a compelling portrait of one man’s life and a pointed critique of the inequalities that support the supposed national prosperity championed by the Tokyo Olympics.

Kazu, an unhoused man living in Ueno Park, was born in the town of Sōma in Fukushima in 1933. In order to support his family, Kazu moved to Tokyo in 1963 as a laborer engaged in the construction of athletic facilities for the 1964 Tokyo Olympics.

Kazu has lived in Tokyo since then, only visiting his family occasionally. When he finally retires and returns to Fukushima, his wife dies seven years later. Not wanting to become a burden to his daughter and granddaughter, Kazu takes the train back to Tokyo. He’s so exhausted when he disembarks at Ueno Station that he simply lies down in the large public park outside the station and goes to sleep. In this way, almost by accident, he becomes homeless. As Kazu reflects:

If you fall into a pit you can climb out, but once you slip from a sheer cliff, you cannot step firmly into a new life again. The only thing that can stop you is the moment of your death. But nonetheless, one has to keep living until they die.

Though Kazu’s story is easy enough to follow, it’s narrated in fragments broken by the conversations of people walking through the park, which juxtapose the comforts of middle-class leisure against the day-by-day existence of unhoused people. The men and women living rough in Ueno Park aren’t abject by any means, as they’re cared for by each other and a network of local communities. Still, their lives are precarious, and they can be ordered to leave at any time.

Tokyo Ueno Station isn’t misery porn. Rather, it’s about helping the reader notice what was always visible. In a rare aphorism toward the end of the novel, Kazu remarks, “To be homeless is to be ignored when people walk past, while still being in full view of everyone.”

In another sense, however, the conversations Kazu overhears in Ueno Park are indicative of how most people living in Tokyo don’t view the unhoused as dangerous. If two middle-aged housewives chatting about their pets don’t care about whether an unhoused person is chilling out on the next bench over, are homeless people really so much of an eyesore? They’re not criminals, so why shouldn’t they have the same right to occupy public space as everyone else?

And why should the police have the right to force the unhoused away from their belongings and their communities every time a member of the imperial family visits the area?

The novel closes with Kazu being kicked out of Ueno Park and forced to seek shelter elsewhere until an imperial visit is concluded. During this intensely uncomfortable period, he suffers a minor stroke and decides to throw himself on the train tracks at Ueno Station, a decision that happens to coincide with the 2011 Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami. In his last moments, Kazu’s spirit returns to the Fukushima town of Sōma, which was directly impacted by the tsunami and resulting nuclear crisis (as documented brilliantly in Ryo Morimoto’s monograph Nuclear Ghost).

Yū’s irony isn’t subtle: the fantasy of “Japan” can only be celebrated if the people who literally build its monuments and provide its energy are hidden away. Tokyo Ueno Station asks the reader to consider the symbol of the Japanese Emperor, as well as the persistence of the ideologies that once supported Japanese military imperialism and continue to marginalize Japan’s own people.

As an American, I will readily admit that this is not my circus, but I can’t deny that Yū’s writing has given me some strong feelings about clowns. To me, it makes perfect sense that Tokyo Ueno Station was awarded the National Book Award for Translated Literature in 2020, right in the middle of the first Trump presidency.

Still, despite the strength of its argument and the sharpness of its critique, I don’t think that shaping political opinion is the point of this novel. Rather, the beauty of Tokyo Ueno Station lies in Kazu’s individual story, as well the fascinating collage of impressions he creates through his observations of the city, which are linked to his experiences growing up in the regional culture of coastal Fukushima. There is value in seeing what is often ignored, and value in documenting quiet voices that are often unheard.

What Yū demonstrates is the value and dignity of small and personal stories, especially in the face of large national narratives that crush the marginalized in the name of progress. Tokyo Ueno Station doesn’t make any sweeping political arguments or engage in polemics, but rather allows the remarkable individuality of Kazu’s story to shine. The brilliance of Yū’s critique is that, while Kazu’s story is his own, his unfortunate fate feels inevitable in the current of larger forces. Despite its literary style and gut-punch ending, Tokyo Ueno Station isn’t a difficult novel to read, but it’s a difficult story to sit with.