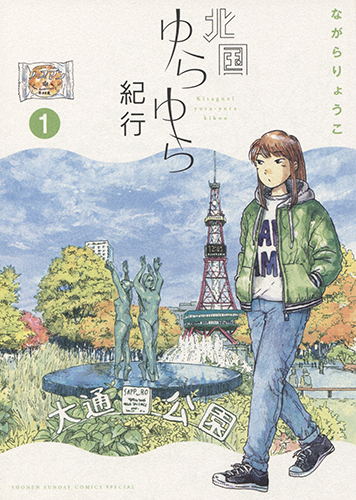

Ryōko Nagara’s Kitaguni yura-yura kikō (北国ゆらゆら紀行) is an episodic travelogue manga that follows a young woman named Tsukiko who left her job to return to her hometown of Sapporo.

Tsukiko is too burnt out to resume full employment, and her savings are running low. Her friend Chitose invites her to move into a Shōwa-era sharehouse co-rented with her flatmate Kensuke and Kensuke’s girlfriend Miwa. Their landlord, a world traveler who no longer lives in Japan, says that Tsukiko can stay if she can manage to clean up all the junk in the spare room.

As Tsukiko recovers from her recent life changes, she and Chitose explore Sapporo at a leisurely pace. Chitose is a writer who aspires to create a magazine celebrating the city’s regional culture. For the time being, she posts articles on her blog and creates zines. Chitose brings Tsukiko along while she scouts for material at small local stores and restaurants. When they’re not out and about, the two women dig through the cardboard boxes left behind by the landlord and uncover all sorts of treasures, from vinyl records to unique Hokkaido woodcrafts.

In my review (here) of Tomoko Shibasaki’s short story collection A Hundred Years and a Day, I touch on the phenomenon of “analog nostalgia,” the fascination with tangible media and the objects of an earlier era. Shibasaki’s collection dwells in a gentle sense of decay, but Kitaguni yura-yura kikō is marked by its youthful energy. As they stroll through beautiful streets lined with old houses and enjoy lively conversations over local cuisine in charming restaurants, it’s clear that Tsukiko and Chitose are thoroughly enjoying themselves.

Despite the fun she has with Chitose and her friends, Tsukiko suffers from depression and anxiety. The tiny apartment she occupies at the beginning of the manga is filled with trash, and she loses track of time while doomscrolling late at night. When Tsukiko considers the possibility of finding a new job, she imagines herself as a defenseless egg yolk sweating and apologizing while surrounded by menacing shadows.

When she invites her friend to move into her sharehouse, Chitose gives Tsukiko something tangible to hold. The manga’s emphasis on analog media, from Chitose’s printed zines to the old Walkman and cassette tapes that Tsukiko digs out of the landlord’s cardboard boxes, isn’t just simple nostalgia. Rather, it’s a concrete solution to a distressingly amorphous problem.

As the anonymous author of one of my favorite video game blogs writes (here) regarding the appeal of retro media, “We weren’t meant to live in an endless feed.” The rituals required by analog media once “gave life a shape that wasn’t constant images on a screen to choose from,” and these rituals serve as an anchor in the flow. Kitaguni yura-yura kikō doesn’t glorify the past or fetishize commodified nostalgia. Instead, tangible objects serve as a visual shorthand for places and relationships that don’t vanish when you close an app.

I don’t mean to suggest that Kitaguni yura-yura kikō is an introspective character study. More than anything, it’s a sweet and gentle travelogue, and it’s very charming. This manga makes me want to visit Sapporo and take long walks and eat delicious food. Still, I appreciate the subtext of the story, which is about readjusting to life lived at a slower pace while relearning how to have a meaningful connection with the place you live, the people who share the space with you, and your own embodied existence.