Title: solanin

Japanese Title: ソラニン

Author: Asano Inio (浅野いにお)

Translator: JN Productions

Publication Year: 2008 (America); 2005 (Japan)

Publisher: Viz Media

Pages: 428

Is manga literature? In some cases, like Urasawa Naoki’s Monster or 20th Century Boys, one could make a very strong positive argument. Some manga, however, like Bleach or Yuzawa Ai’s Nana series, are nothing more than once promising but now over-bloated cash cows. On the other hand, many of my favorite manga, like Azuma Kiyohiko’s Yotsuba&!, are not literature simply because they are masterpieces of a completely different art form.

But Asano Inio’s 420 page work Solanin is literature, no doubt about it. Like many Japanese narratives, it is driven not so much by plot as by character development and a fascination with the beauty of everyday life, which sounds like a Hallmark greeting card but is actually quite gritty and satisfying. Unlike a great deal of manga, Solanin deals with the problems of Japanese young people who are not sailor-suited schoolgirls and have already passed through their fun and fancy-free college years. In other words, the protagonists of Solanin have already grown up, or at least are trying to. I suppose that, in this way, Solanin is like a more focused and mature version of Umino Chika’s popular shōjo manga Honey and Clover, which chronicles the struggles and heartbreaks of a group of friends who have just graduated from art school.

As I said, there isn’t much to discuss in terms of plot (although there are some fairly gut-wrenching twists in the story), but the basic premise of the manga is that the protagonist, Mieko, who has just graduated from college and moved in with her boyfriend, has gotten sick of her boring office job and creepy boss and decided to quit working for a few months. During this time, she focuses on her friends and boyfriend, who had formed a rock band together in college. Mieko wants her guitarist boyfriend Naruo, who also feels suffocated at work, to get the band back together and be more serious about his music and his dreams, which drives the story forward but causes tension between the two. What ends up happening is way beyond what the characters – or the readers – suspect. The ending of the manga isn’t happy, necessarily, but it is fulfilling.

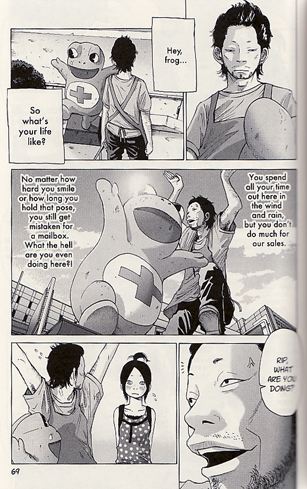

Although the focus of the narrative is on Mieko, occasionally chapters will be told from the point of view of another character, like Mieko and Naruo’s friends Rip (the drummer) and Kato (the bassist). These chapters rarely have anything to do with the main story but are still interesting, especially in how they highlight different aspects of the group dynamic within the circle of friends. The alternate narrative chapters also provide the majority of the manga’s comic relief, which is actually quite funny in a quiet sort of way.

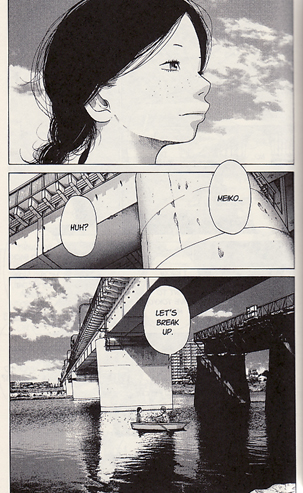

Although the characters and narrative style alone make Solanin worth reading, what really made me pick up this book and buy it was the artwork. The character designs, though simple, are very appealing. I also feel that, within the limits of Asano’s personal style, they are realistic in the way they depict different body types and facial expressions. The background art is wonderfully realistic, which is extraordinary when you realize how much of it there is. Unlike most manga, which only provide a panel of background art every page or two, Solanin is filled with beautiful drawings of the scenery and landscape of the Tokyo suburbs. Even if you think Solanin’s story is just basic Banana Yoshimoto style angsty emo crap (although, in my mind, it never gets that bad), the artwork makes the whole thing worthwhile. Really, it’s gorgeous.

So, although the cover isn’t that appealing, and although the $17.99 price tag is pretty hefty, I can’t recommend this book enough. I’m really happy I gave it a chance, despite my misgivings.

Just to give a feel for the art style, I’ll post some images from the manga. I apologize for the poor scanning quality…