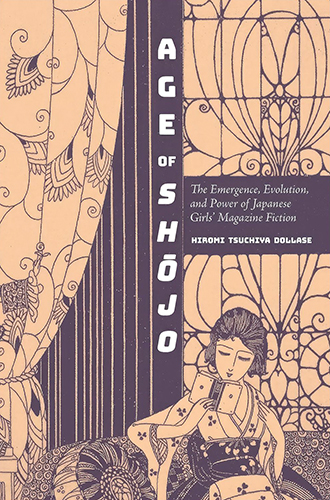

Numerous articles and book chapters have explored the origins of shōjo culture, and Hiromi Tsuchiya Dollase’s Age of Shōjo: The Emergence, Evolution, and Power of Japanese Girl’s Magazine Fiction contributes new insights while weaving these threads together into a tapestry depicting the history of how imagined communities of young women were shaped by the editors and contributors of popular mass-market magazines in Japan.

Age of Shōjo opens with a discussion of Louisa May Alcott’s novel Little Women, which was translated by Kitada Shūho in 1906 as Shōfujin. Through a close reading that compares the translation to the original, Dollase demonstrates how the novel “introduced a Japanese female audience to Western lifestyle and the image of a Western home” while still conforming to native Meiji-era constructions of femininity.

Chapters Two and Three introduce two key figures who helped shepherd amateur women’s fiction into professional venues. The first is Numata Rippō, who edited the seminal magazine Shōjo sekai (Girls’ World), and the second is Yoshiya Nobuko, who is famous for her contributions to this magazine, which were later published as the collection Hana monogatari (Flower Tales).

Chapters Four and Five trace the development of the portrayal of gender and sexuality in Yoshiya’s work in comparison with her contemporaries Morita Tama and Kawabata Yasunari, who also contributed short fiction to popular magazines such as Shōjo no tomo (Girls’ Friend) during the 1930s and early 1940s.

Chapter Six jumps forward to the immediate postwar era, when girls’ magazines such as Himawari (Sunflower) were filled with romanticized images of the United States, and Chapter Seven chronicles how magazine fiction for teenagers took a more mature turn during the 1980s. The stories published in the 1980s were still commissioned, selected, and edited to appeal to a readership of young women, but this fiction now addressed themes relating to women in the workforce, including frustrations concerning the choice between marriage and a career.

As related by the anecdotes in the book’s Introduction and Afterword, girls’ fiction continues to be widely read and culturally influential in Japan. Dollase handles this material with respect and care by acknowledging its problematic aspects but preferring to contextualize instead of critique. This is especially the case with the heavily censored fiction of the 1940s, as well as the work of writers whose stories were progressive when they were first published but may seem socially conservative now.

In her informative study of these texts, Dollase demonstrates how, “through magazine stories and illustrations, readers came to acknowledge themselves as shōjo, a new cultural identity,” and how the fiction of these authors contains “messages of resistance against disagreeable cultural conditions cloaked in fantasy, sentimentalism, and humor.” Along with Dollase’s deft and accessible analysis, Age of Shōjo’s annotated reproductions of magazine covers and interior illustrations are a gift to readers interested in the literature and visual culture of girlhood in twentieth-century Japan.