Shigeru Mizuki was one of the twentieth century’s most prolific and influential manga artists. Today he’s known primarily for documenting the culture and folklore of his childhood in rural western Japan. The single-volume graphic novel NonNonBa, originally published in 1992, is perhaps Mizuki’s most accessible work, as well as a fantastic gateway into the study of indigenous Japanese religion and folklore.

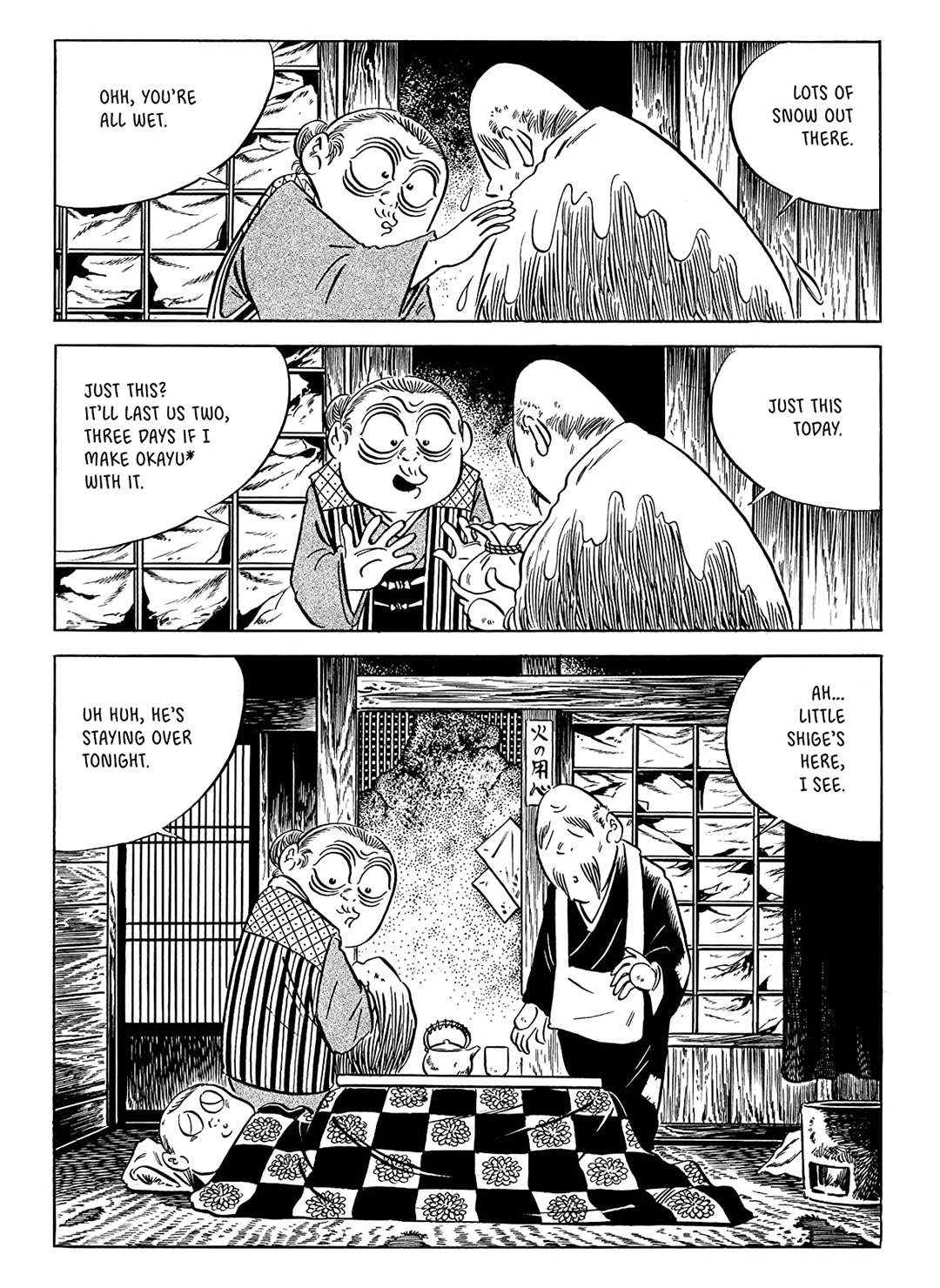

NonNonBa tells a coming-of-age story about the artist’s childhood relationship with an elderly family friend, the poor but kind Nonnonba of the title. Nonnonba is a repository of local folklore, and she sincerely believes in yokai, a term that refers to any number of species of Japanese fantastical creatures. The world of NonNonBa is indeed populated with yokai, but the manga is primarily a realistic account of life during the early 1930s.

NonNonBa opens with an introduction to the coastal town of Sakaiminato in the Kansai-region prefecture of Tottori. Despite being a port on the East Sea, the town wasn’t wealthy, and most houses remained unchanged from the nineteenth century. Mizuki’s family was relatively comfortable, and he lived with his mother, his two brothers, and his father, who worked at a bank but had creative ambitions and operated a small cinema on the side. Nonnonba was occasionally employed by the family to help with housework and childcare, as she was by several families in town.

The artist, who goes by the name of Shige, is a mediocre student but deeply fascinated by the natural world, often bringing home strange objects like animal bones in order to study and draw them. When he’s not at his desk, Shige plays at being a soldier in the “boy army” that roams around the town and beach staging pretend wars with other roving bands of children.

Shige’s uncomplicated boyhood is disrupted by Chigusa, a cousin from Osaka who is sent to Sakaiminato to recover from tuberculosis. Nonnonba cares for Chigusa while she’s bedridden, and the girl is just as interested in Nonnonba’s yokai stories as Shige is himself. The two become friends, and Shige is heartbroken when his cousin succumbs to her illness. He begins drawing in earnest, no longer as invested in the boy army as he once was.

After losing Chigusa, Nonnonba begins working for a family from the city that has moved into a house rumored to be haunted. She’s charged with the care of Miwa, a young girl who lives in the family’s house and seems to be able to see and hear yokai. Shige believes the girl is a victim of human trafficking, which seems highly likely given the number of other young girls who have passed through the house. Regardless, there’s not much he can do about this as a young boy.

As he develops a close friendship with Miwa, Shige matures, and he understands that growing up isn’t growing away from yokai, but rather realizing that the stories of these creatures are part of a much larger world. Despite their flaws, Shigeru’s mother and father are both portrayed sympathetically, as are his brothers and friends. NonNonBa overflows with sympathy and compassion, gently poking fun at the characters while also encouraging the reader to see them in their best light.

Despite being published more than thirty years ago, NonNonBa doesn’t feel dated. The stylizations of Mizuki’s artwork are timeless, and his character designs are clean and fresh. The high quality of Jocelyne Allen’s translation contributes to the contemplative yet entertaining tone of the story, whose episodes move briskly but never feel cartoonish.

Through Mizuki’s sensitive storytelling and evocative artwork, NonNonBa celebrates how folklore inspires imagination and facilitates resilience in the face of loss and change. Despite the occasionally heavy subject matter, this graphic novel is accessible to readers of all levels, and I imagine it would be a fantastic text to spark discussion about history, family, and folklore in the classroom.