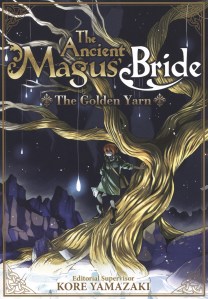

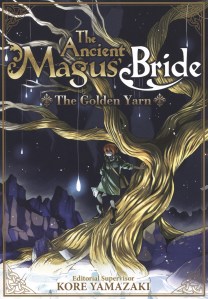

The Ancient Magus’ Bride: The Golden Yarn

Japanese Title: 魔法使いの嫁 金糸篇 (Mahōtsukai no yome: Kinshi hen)

Editorial Supervisor: Kore Yamazaki (ヤマザキコレ)

Translator: Andrew Cunningham

Publication Year: 2017 (Japan); 2018 (United States)

Publisher: Seven Seas

Pages: 349

The Golden Yarn collects eight short stories set in the world of The Ancient Magus’ Bride, an urban fantasy manga series that was adapted into a three-part anime OVA in 2016 and a television series that aired in 2017. Even though I’m only a casual fan of the franchise, I still found this collection delightful. Each of the stories stands on its own, and the book is accessible even to people entirely unfamiliar with the manga or its animated adaptations.

The first story, “Frozen Flowers,” is by Kore Yamazaki, the artist who created the Ancient Magus’ Bride manga. Like the other stories in The Golden Yarn, “Frozen Flowers” offers a glimpse into the world of the series without assuming any prior knowledge. In this story, a centaur named Hazel visits his aunt Marie, who was born with two feet instead of four. Marie looks like a normal human, but she has the heart and mind of a centaur, and she wants nothing more than to run under the open sky with the rest of her herd. Because of her appearance, however, she’s ostracized by her fellow centaurs and lives alone in an isolated area in rural England. It’s difficult for Hazel to understand why Marie doesn’t try to pass as human, but he still accepts her and offers her his friendship and kindness.

“Frozen Flowers” introduces the main theme of The Ancient Magus’ Bride, which is the various relationships people negotiate with difference. Some of these relationships are healthy and affirming, as in “Frozen Flowers,” while others are toxic and exploitative.

There’s a strong current of horror running through the stories in The Golden Yarn. It’s most present in Jun’ichi Fujisaku’s “The Man Who Hungered for Trees,” in which the assistant to a genius video game programmer uncovers the sinister roots of his supervisor’s talent. The programmer makes small blood sacrifices to the spirits of marijuana bushes in exchange for energy and inspiration, but the plants are hungry for larger prey. As you might imagine, this doesn’t end well for anyone involved.

All of the stories in The Golden Yarn were contributed by authors associated with various light novel series. I was especially impressed with “The Sun and the Dead Alchemist,” which was written by Kiyomune Miwa, the author of the steampunk zombie-hunting series Kabaneri of the Iron Fortress (which was adapted into an anime in 2016). Miwa haunts similar grounds in this story, which describes the bittersweet romance between a necromancer and a young woman whom she inadvertently destroys with her magic.

An interesting aspect of this collection for me, as an American, was the opportunity to look at Europe and America from an outside perspective. For example, the venerable Yuu Godai, the author of the long-running Guin Saga series of dystopian fantasy novels, contributed a piece called “Jack Flash and the Rainbow Egg,” which is about a fairy who lives in New York but is obsessed with Japanese popular culture and sets up a detective agency to earn human money in order to buy dōjinshi. Godai’s energetic adventure story is a fun take on American culture, but what I found even more intriguing than a New York run by magical secret societies is the fantasy of twenty-first century Great Britain as a mystical land of rolling green fields, garden cottages, and magical creatures. I suppose The Golden Yarn is sort of like Harry Potter without the overt allusions to class conflicts and real-world fascism, but none of the stories shy away from the darker side of human nature.

Seven Seas has also published a companion volume, The Ancient Magus’ Bride: The Silver Yarn. Aside from the second half of “Jack Flash and the Rainbow Egg,” The Silver Yarn can be read independently, and its stories are just as engaging as those in The Golden Yarn. I can happily recommend both of these short story collections to any fan of historical fantasy and contemporary urban fantasy regardless of their level of familiarity with the Ancient Magus’ Bride franchise. Although there’s no explicit mention of sexuality, some of the stories are quite violent and disturbing, and the books are best suited to older teens and adults.