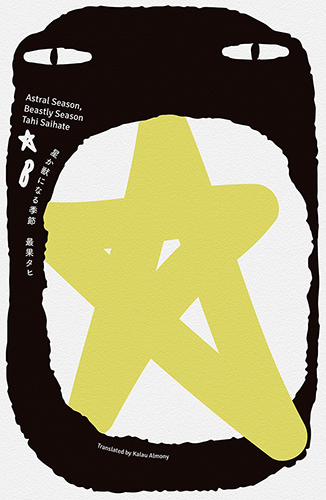

Tahi Saihate’s Astral Season, Beastly Season (translated by Kalau Almony) is a novella about toxic high school friendships and girl group fandom gone horribly wrong.

In the first half of the book, a junior in high school named Yamashiro writes a letter to an unpopular “underground idol” named Mami Aino. Mami, who is still in high school herself, was arrested on the charge of murdering her ex-boyfriend. Another boy in Yamashiro’s class, Morishita, takes the news poorly and decides to commit a series of copycat murders so that he can confess to the crime Mami committed and take the fall in her place.

Unlike Yamashiro, Morishita is attractive, popular, and a model student. Why he’s a fan of a fledgling girl group with such a small following is unclear, and it seems like an incredible coincidence that both Yamashiro and Morishita would be attracted to the same super-indie performer. Although Yamashiro doesn’t seem to be aware of this, I strongly suspect that Morishita is much more attracted to Yamashiro than he is to Mami.

Regardless of motive, Morishita’s intention to commit murders is sincere, and he wastes no time getting started on his grim task.

The second half of the book takes place several years later, when Morishita’s childhood friend Aoyama meets up with Watase, a high school classmate of one of Morishita’s victims. Watase accuses Aoyama of portraying the murderer as “an all-around good guy” in an interview he gave to a tabloid magazine, and she wants him to apologize. Before the two of them get a chance to have a proper conversation, Aoyama is contacted by the brother of another of Morishita’s victims. This young man also wants closure, but what was going on in Morishita’s head will forever remain a mystery.

I have to admit that Astral Season, Beastly Season left me cold. More than anything, this is a book about the friendship dynamics of a small group of high school students. The novella doesn’t dwell on the psychology of the criminals, nor does it offer much description of what underground idol culture is or what it’s like to participate in this sort of fandom.

Instead, the reader is inundated with inane details about who is friends with whom, and who does and doesn’t walk home together, and who ignores other people on the train, and who went to a café together, and who is and isn’t talking to whom, and who said something mean after class, who doesn’t want to be in a group together on a school trip.

Amidst the swirl of teen friendship drama, the actual murders seem like little more than an afterthought. Were it not for the second half of the book, one might even argue that Yamashiro and Morishita are just pretending to plan and commit crimes. In fact, I tend to think that the story might actually be more interesting if this were the case. None of the characters has anything particularly insightful to say after the time skip, and the reader never learns anything about what Mami or Morishita might have been thinking or feeling. It’s all a bit disappointing.

There are two points of comparison that might bring the novella’s story into sharper contrast. The first is Yukio Mishima’s classic novel The Temple of the Golden Pavilion, a psychological drama about the (heavily fictionalized) young man who set fire to the eponymous landmark in 1950. It’s a gorgeous piece of writing, and Mishima is fascinated by the mind of a teenage loner who commits a serious crime, especially with respect to how this crime results from an intense homoerotic friendship. Another interesting companion novel is Rin Usami’s Idol, Burning (which I reviewed here), which I feel offers a much more sensitive and astute portrayal of the role that pop music fandom can play in the life of an emotionally precarious teenager.

I get the feeling that Astral Season, Beastly Season might have benefitted from a translator’s afterword explaining who the writer is and what the context for her work might have been. It might be a worthwhile project to discuss this novella in a college class or an academic paper, especially given Tahi Saihate’s status as an internet-famous visual artist who uses text to create eye-catching public art installations, but I’m not sure it stands on its own as a work of fiction.

If nothing else, the novella is painfully honest about how high school friendship drama can feel life-shattering and world-changing to the people involved. Still, whether this sort of story is worth spending time with really depends on the interests and taste of the reader. It wasn’t for me, but perhaps a younger reader might feel a stronger sense of immediacy and connection to a beautiful high school boy who commits terrible crimes.