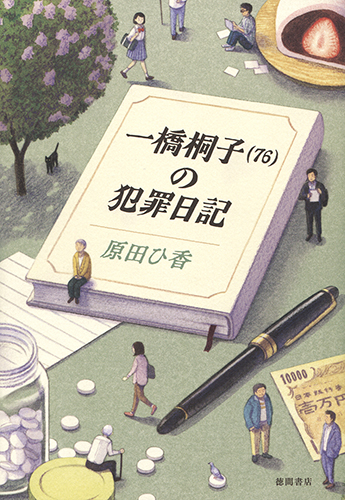

Hika Harada’s 2020 novel Hitotsubashi Kiriko (76) no hanzai nikki, which I’ll refer to as “Kiriko’s Crime Diary,” is the story of the eponymous Kiriko Hitotsubashi, who has found herself alone and in trouble at age 76. After her closest friend dies and her life savings are stolen, Kiriko decides that her best option is to spend her remaining years in prison. The only problem is that, before she goes to prison, Kiriko first needs to commit a crime.

Kiriko has been single all her life, but she jumps at the chance to share a house with her best friend Tomo, whose husband has died of a heart attack. Unfortunately, after two years of friendly companionship, Tomo dies of cancer, and Kiriko’s signature seal, bank passbook, and account holdings are stolen by a young man who asks to enter her house to pay respects to Tomo’s memorial. To add insult to injury, Tomo’s two sons treat Kiriko like garbage as they remove the furniture and cookware she shared with Tomo from her house.

Kiriko is left destitute, and she’s forced to use the last bit of money she has left to rent a subsidized apartment in a privately owned building for the elderly. She can barely afford groceries, and her new neighbors are difficult and unpleasant. Despite her age, Kiriko is as healthy as a horse, and she doesn’t seem to be in any danger of dying soon. She decides that being in prison would be preferable to becoming homeless, so she resolves to live a life of crime.

For the most part, Kiriko’s Crime Diary is a comedy that follows a sweet-natured and sensible woman as she does her best to get arrested. Kiriko has standards, and she doesn’t want to commit any sort of crime that might cause actual harm. She tries shoplifting from a chain grocery store, counterfeiting money with a convenience store photocopier, and scouting targets for a dubiously legal moneylender – all to no avail.

Over the course of her attempts to solicit advice regarding how to commit a crime, Kiriko ends up befriending all sorts of people, from the owner of the office building where she works as a janitor to a high school girl who volunteers to be kidnapped to punish her negligent parents. Between one thing and another, Kiriko ends up attracting the attention of a semi-retired yakuza boss, who uses intermediaries to contact Kiriko before finally meeting her in person.

One of the major subplots of the novel involves a man around Kiriko’s age who becomes entrapped in an elaborate “marriage scam” by a younger woman who drains his finances and then disappears. The man is crushed by disappointment, and the members of the poetry club Kiriko once attended with her friend Tomo have to band together to figure out how to help him. Along with Kiriko’s own troubles, this episode highlights the lack of a social safety net for many elderly people in Japan.

The theme of elder precarity becomes especially critical with the approach of Kiriko’s 77th birthday, which marks the start of her formal age of retirement. The janitorial company that employs Kiriko forces her to quit, depriving her of her only means of supporting herself. If Kiriko has no job and no one to serve as a guarantor for her rental contract, what is she supposed to do, exactly? Is her only recourse to start working with the yakuza?

Thankfully, Kiriko’s Crime Diary has a happy ending. All of Kiriko’s friends show up during a climactic scene to offer support and advocacy, and Tomo’s daughters-in-law apologize for the way she was treated by her late friend’s sons. All the loose ends are neatly tied, and Kiriko might even get to have a lovely winter romance with the handsome yakuza boss. I usually shy away from this sort of sentimentality, but why shouldn’t Kiriko have the best of all possible endings?

When I was working on one of my dissertation chapters about Natsuo Kirino’s gritty crime novel Grotesque, one of my readers asked me why Kirino’s characters all have to be so miserable. That was a fair question, and my answer was something along the lines that Kirino’s novels express the reality of the despair faced by many older adult women who find themselves completely devalued by society.

While I still believe that the tonal bleakness of Kirino’s style of critique is necessary and important, I also think that the happy ending of Kiriko’s Crime Diary is a welcome counterpoint. What Harada archives through this gentle comedy is to model one possible solution to elder precarity. Namely, if the neoliberal Japanese state is so utterly useless in providing social welfare, people must aggressively resist twentieth-century social conventions to form communities for mutual aid.

This support benefits not just elderly people, but also multigenerational networks. As much as Kiriko gains from her friendships with the owner of the building she cleans and the teenage girl she “kidnaps,” these characters also benefit from having Kiriko in their lives. It would be a shame, Harada suggests, not to have at least one friend like Kiriko.

Relearning how to make friends while relying on the kindness of strangers isn’t going to be a feasible solution for everyone, of course, but it’s a damn sight better than going to prison. And, if someone like Kiriko is considering prison, what are we even doing as a society? Even with a marvelously happy ending, Kiriko’s Crime Diary offers a social and political critique that’s difficult for even the most conservative reader not to agree with.

Hika Harada has enjoyed a productive career, and she’s won numerous awards for her fiction and screenplays. It’s no surprise that Kiriko’s Crime Diary was a bestseller that has found a place on all sorts of recommendation lists. This story will definitely appeal to readers outside of Japan, and it’s perfect for the same readership that enjoyed Killers of a Certain Age (which is fantastic, by the way).

Harada’s novel Dinner at the Night Library is going to be released in English translation in September 2025, and I’m looking forward to reading it. Kiriko’s Crime Diary is a genuinely fun and charming story, and I’d love to see it appear in translation too.