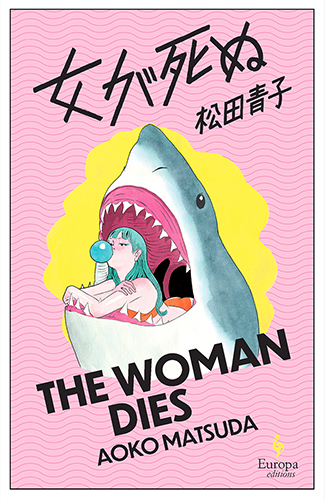

The Woman Dies presents 52 pieces of flash fiction by Aoko Matsuda, the author of the short story collection Where the Wild Ladies Are. Each of Matsuda’s small but sparkling stories responds to various aspects of pop culture in clever and surprising ways.

Characteristic of Matsuda’s idiosyncratic approach to the flotsam of contemporary culture is “Hawai’i,” which imagines a heaven for clothes that were thrown away because they did not spark joy. The heaven enjoyed by an unworn sweater sounds like a lovely time of relaxing by the pool while, in the sky, “not far from the rainbow, the pair of skinny jeans owned in similar shades was paragliding together with the dress once worn to a friend’s wedding and never again.”

At the same time, the over-the-top language Matsuda uses to describe this paradise hints at how ridiculous it is to ascribe any sort of teleological meaning to consumerist excess. Still, if this is the world we find ourselves in, why not imagine a heaven where even a discarded sweater is allowed to have a happy ending?

While the topics covered in The Woman Dies are varied, many of the stories playfully confront gender issues in popular media. One of the more intriguing of such stories is “The Android Whose Name Was Boy,” which Matsuda writes “evolved from my thoughts about Neon Genesis Evangelion,” a classic sci-fi anime from 1995 that does indeed inspire thoughts about gender.

The eponymous android, whose name is in fact “Boy,” begins its life by setting out on an adventure. Over the course of the five-page story, it does its best to disrupt narrative conventions regarding young male characters. Challenging and unending though this task might be, “the android whose name is Boy, developed to heal the wounds of those hurt by boys hurt in the past, is on the move once more.”

While “The Android Whose Name Was Boy” is open to a diversity of interpretations, other stories in the collection are overtly feminist. In “The Purest Woman in the Kingdom,” a prince takes it upon himself to seek out a woman who has never been touched by a man. After a great deal of searching, he finally finds and marries one such woman. On their wedding night, she karate chops him into oblivion. This woman has never been touched by a man; and, thanks to her training and skill in martial arts, she never will be. Absolute queen behavior.

Most of the stories in The Woman Dies are relatively lighthearted, but “The Masculine Touch” (by far my favorite piece in the collection) is out for blood. This story flips the script on gender, casting male writers as delicate greenhouse flowers who need to be supported because sometimes – every so often – their work has cultural and economic value. Matsuda doesn’t pull her punches:

The more radical of the male novelists wrote articles about this turn of events for male magazines, declaring this the beginning of the Male Era. They bolstered their arguments with examples of the other times when the masculine touch had effected changes like this one, thus arguing for men’s continued progress in all areas of society.

“The Masculine Touch” responds to a painfully specific way of talking about female writers and artists in Japan, and I imagine that people in other contexts can relate to frustrations regarding how the publishing industry fetishizes “queer writers,” or “writers of color,” or any number of people whose humanity is compressed into marketing-friendly categories.

Unfortunately, other pieces in the collection lack this specificity. Though we’re all familiar with the trope of fridging female characters, the title story, “The Woman Dies,” is a bit too broad to resonate. Though it’s easy to sympathize with the sentiment underlying “The Woman Dies,” readers may find themselves simply shrugging and moving on. Flash fiction tends to be hit or miss, but this collection offers an array of stories to choose from, and it achieves an admirable balance between heavy hitters and palette cleansers.

The Woman Dies is remarkably cohesive as a collection. There’s a lovely rhythm and flow to the stories, and it’s just as entertaining to read the book in one sitting as it is to dip in and out at your leisure. Matsuda’s writing is sharp and self-aware, and she uses brevity as a weapon to puncture the absurdities of gender, media, and modern life. It’s a pleasure to read her work in Polly Barton’s translation, which is quick and lively and showcases an incredible range of tone and style that’s pure literary pop.