Title: The Columbia Anthology of Modern Japanese Literature, Abridged Edition

Editors: J. Thomas Rimer and Van C. Gessel

Poetry Editors: Amy Vladeck Heinrich, Leith Morton, and Hiroaki Sato

Publication Year: 2011

Publisher: Columbia University Press

Pages: 960

The Columbia Anthology of Modern Japanese is the most comprehensive anthology of Japanese literature since the mid-nineteenth century; but, with two enormous (and expensive) volumes, it’s a bit daunting for all but the most stalwart of readers. I was therefore excited to learn that an abridged softcover version of the text has been released. At almost a thousand pages, the anthology still isn’t for the casually interested. As it provides a much wider selection of writers and genres than every other anthology of modern and contemporary Japanese literature on the market, however, The Columbia Anthology is an invaluable resource not only for students of Japanese literature but also for anyone interested in Japan in any capacity.

The anthology is divided into six sections spanning from the beginning of the Meiji period in 1868 to the end of the twentieth century. The two sections devoted to the Meiji era include work by naturalists and playwrights such as Mori Ōgai, Shimazaki Tōson, Kunikada Doppo, and Nagai Kafū, as well as essays by Natsume Sōseki, including “The Civilization of Modern-Day Japan.” The anthology then proceeds into the interwar period, which includes the work of authors such as Akutagawa Ryūnosuke, Edogawa Rampo, Kawabata Yasunari, and Tanizaki Junichirō. The section titled “The War Years” is mercifully short but includes stories by Dazai Osamu, Ishikawa Tatsuzō, and Ōoka Shōhei.

The “Early Postwar Years: 1945-1970” section is the longest in the anthology and reads like a hit parade of famous postwar writers such as Abe Kōbō, Enchi Fumiko, and Mishima Yukio. Many well-known postwar joryū bungaku (“women’s literature”) writers, such as Hayashi Fumiko and Kōno Taeko, are represented as well. The last section collects contemporary literature from the seventies, eighties, and nineties by both internationally famous authors such as Murakami Haruki and Ogawa Yōko and writers who are prolific and well known in Japan, such as Hoshi Shinichi and Furui Yoshikichi.

What is wonderful about this anthology is that, unlike other anthologies of modern and contemporary Japanese literature, it includes lengthy selections of Japanese poetry, both in “traditional” forms (such tanka and haiku) and in more modern forms (such as free verse). Although I am not a connoisseur of poetry in translation and thus can’t vouch for the quality of The Columbia Anthology‘s selections, I am thankful that so many works of modern and contemporary Japanese poetry have been brought together in a single volume. The majority of the original publications in which these translations appeared have long since gone out of print, so The Columbia Anthology is perhaps the best way to familiarize oneself with a rich yet underappreciated body of literature. The anthology also includes dramatic scripts by playwrights and screenwriters such as Inoue Hasashi and Kara Jūrō, texts which are also difficult to find elsewhere.

My enthusiasm for The Columbia Anthology is genuine, but some of the editors’ comments in the Preface shed light on some of the more conservative politics of literary anthologization. For example, to justify the entry of their project into a field in which many anthologies already exist, Rimer and Gessel state:

One difference between this volume and some of the earlier collections is related to the evolving view of both Japanese and foreign scholars as to what constitutes “literature.” Many of the earlier collections sought, consciously or unconsciously, to privilege the long and elegant aesthetic traditions of Japan as they were transformed and manifested anew in modern works. […] But many other kinds of writing, ranging from detective stories to personal accounts – always valued by Japanese readers but neglected by translators in the early postwar decades – can now be sampled here.

Expanding the scope of what is considered literature through diversity in anthologization is always good, of course, but two paragraphs earlier, the editors also made this strange comment:

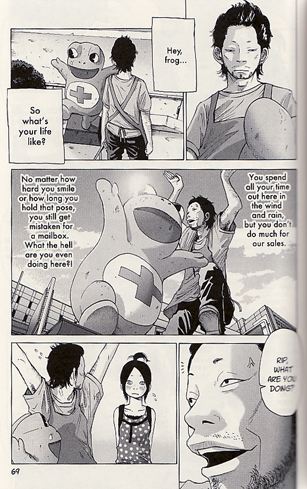

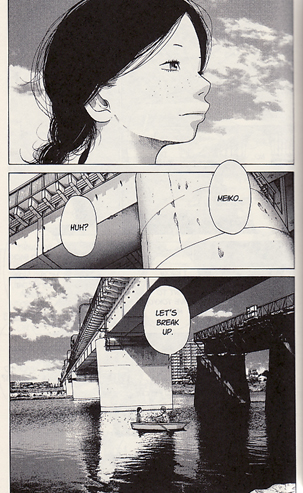

Whatever the level of young people’s interest in manga (comics) and video games may be, literature, as opposed to simple entertainment, often remains the best way to grapple with the problems, and ironies, of the present generation of Japan.

On reading this sentence, I somehow managed to raise an eyebrow and roll my eyes at the same time. The context of this statement was a defense of the strength of contemporary literature in the face of a weighty literary tradition, but I wonder why the editors needed to make the distinction between “literature” and “entertainment” at all. Some types of print culture (such as dramatic scripts) are literature, but others (such as the text portions of visual novels) are not? Edogawa Rampo’s grotesque short stories are literature, but Otsuichi’s horror fiction is not? Haiku are literature, but tweets are not? And – most importantly – manga is not literature? Seriously?

Despite the editors’ stated desire to expand the scope of what is considered literature, their literary politics are, as I stated earlier, quite conservative. Popular fiction by writers like Murakami Haruki and Yoshimoto Banana is included in the anthology, but the work of such writers has been so resolutely canonized by scholarly articles and inclusion in course syllabi that its anthologization comes as no surprise. It’s good to have “outsider” writers like Tawada Yōko and Shima Tsuyoshi included in the anthology, but all of the volume’s stories more or less fit neatly into the category of “literary fiction.” You will not find the cerebral science fiction of Kurahashi Yumiko, or the historical revisionings of Miyabe Miyuki, or the fantastical explorations of Asian-esque mythology of Uehashi Nahoko, or the socially conscious mystery stories of Kirino Natsuo in The Columbia Anthology. You also won’t find any prewar popular fiction, such as the short stories of Yoshiya Nobuko.

This leads me to another criticism I have concerning the anthology, which is that it is remarkably dude-centric. Until the last two sections of the text (“Early Postwar Literature” and “Toward a Contemporary Literature”), there are no female writers represented (save for Yosano Akiko, who has a few poems about flowers and vaginas); not even one of Higuchi Ichiyō’s short stories is included. In the anthology’s defense, many of the women writing before and during the Pacific War, such as Enchi Fumiko and Hirabayashi Taiko, are included in the “Early Postwar” section. Unfortunately, this means that their more overtly political work has been passed over for stories that focus more on “traditional” women’s issues like female sexuality and the family. Furthermore, even though I applaud the editors for including literary essays in their anthology, it frustrates me that not a single one these essays was written by a woman, despite the fact that many female authors – including those represented in this anthology – are extraordinarily well known for their essays. What the editors has done is the equivalent of collecting the most influential essays on literature in North America and leaving out something as important and groundbreaking as Margaret Atwood’s On Being A Woman Writer.

In the end, though, I stand by my assessment of the abridged edition of The Columbia Anthology of Modern Japanese Literature as an essential resource to students of Japan. The volume contains many excellent stories, poems, essays, and dramatic scripts that are difficult to find elsewhere, and the editors keep their introductions of writers and literary epochs brief and to the point. As long as this text is supplemented to bridge over its gaps and omissions, I can imagine it becoming the backbone of a respectable introductory course on modern and contemporary Japanese literature, as well as a source of out-of-print translations of the work of less widely taught authors.

Review copy provided by Columbia University Press.