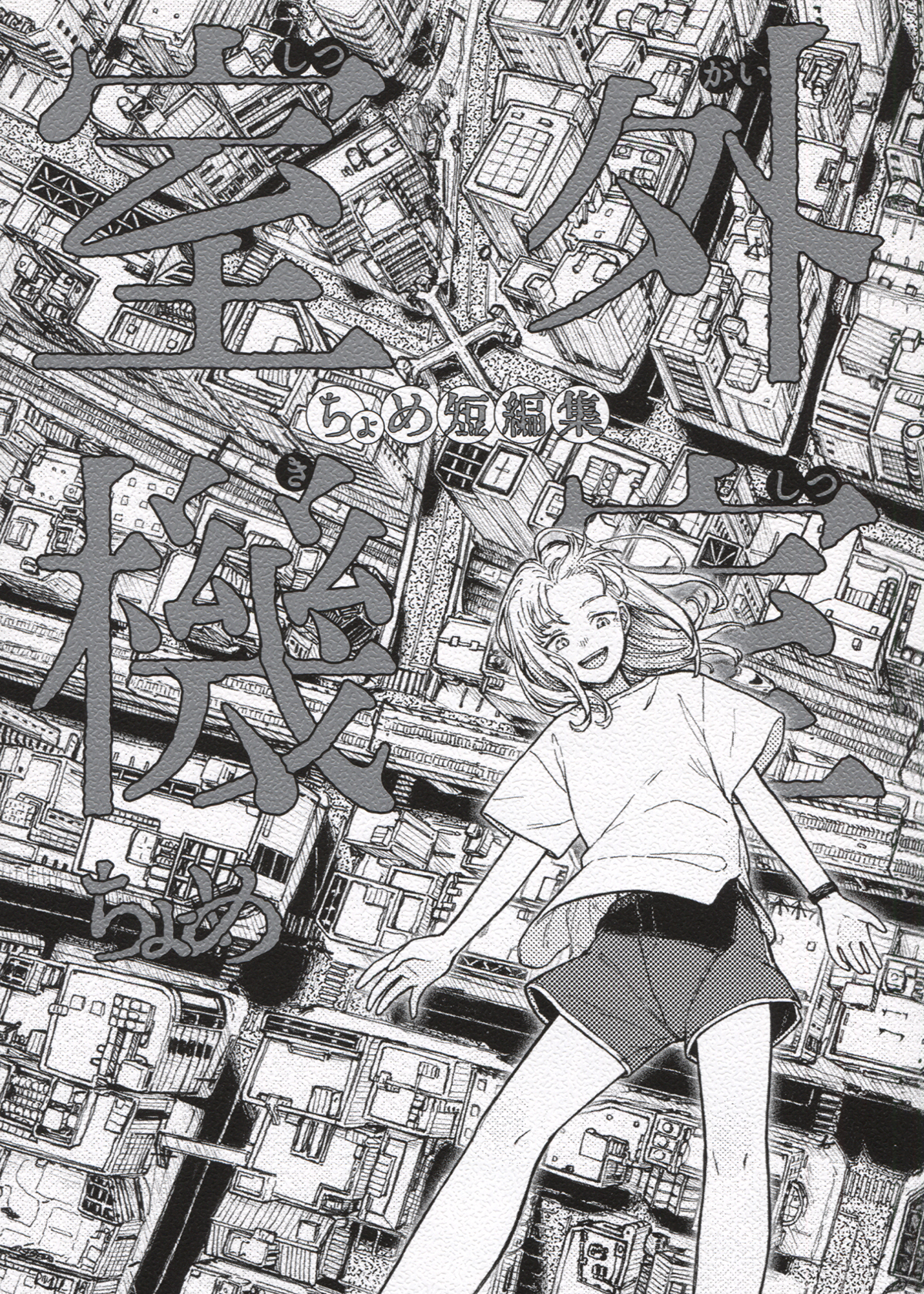

Atsuhiro Yoshida’s 2025 short fiction collection #Tokyo Apartment brings together 21 stand-alone stories about people living in and around Tokyo. The characters are usually living on their own, almost always in retro buildings removed from the city center. There’s very little wealth or glamor in these stories, but their protagonists nevertheless manage to become swept up in the magic of a densely populated megacity.

A representative story is Tokage-shiki gomuin kaisha (“Lizard-style rubber stamp company”), whose narrator recalls a time when he lived in a building that was once famous for being the largest apartment complex in Japan. The building had multiple floors of businesses, and the narrator worked at one of them as an apprentice to an artisan who took commissions for document signature seals. While dining at his favorite pubs in the same building, the narrator grew friendly with a woman who also worked there. He courted her by sending letters to her apartment – which was naturally in the same building. This story perfectly captures the flavor of the comfortably chaotic retro spaces of the old business/residential complexes of West Tokyo.

Not all of the stories are so cozy, however. Sutorei kuriketto (“Stray cricket”) is about a young man with no money, no friends, and no real prospects for finding a decent job. For the time being, he washes dishes in a small diner. He doesn’t have much room in his life for hobbies, but every night he brings back scrabs of cabbage to feed to a cricket that has entered his tiny apartment through a ventilation shaft. While listening to the cricket chirp in the darkness, the narrator is inspired to help the tiny creature find its way back outside. He might have nowhere to go in his own life, but at least the cricket can be happy and free.

Many of the stories end on a more ambiguous note. In Heya o kimeta hi (“The day we decided on an apartment”), two single fathers become online friends as they swap stories and advice with one another. In time, they become real-life friends and begin sharing childcare responsibilities. They mutually arrive at the conclusion that their lives would be easier if they lived in the same apartment building, so they hire a realtor to find a suitable property. There’s something about this sort of housing decision that feels final, however, and this causes the two dads to wonder if they’re really ready to take such a momentous step into the beginning of middle age.

For the most part, the stories in #Tokyo Apartment are fairly mundane, but there are occasional touches of magical realism. In Yūrei no denwa (“Ghost telephone”), the character Moriizumi returns from Yoshida’s novel Goodnight, Tokyo. Moriizumi manages a service that helps people dispose of their old telephones, which often have too much sentimental value to throw away. In a conversation with a crow who makes nightly visits to her balcony, Moriizumi reflects on how analog technology can feel haunted by the ghosts of people with whom our connections have faded. The crow, who is a connoisseur of the unused objects people dispose of on their balconies, agrees with Moriizumi but prefers to focus on making new connections.

A word I often see in reviews of Atsuhiro Yoshida’s writing is yomi-yasui, or “easy to read.” Yoshida has spent more than a decade carefully cultivating a light and precise writing style, and #Tokyo Apartment is indeed a relaxed and chill reading experience. It’s entertaining to encounter such a wide range of variations on the theme of “apartments in Tokyo,” especially since the narrative voices of these stories are so distinct – which is no mean feat when accomplished within the simplicity of the author’s characteristic style.

As an aside, I might recommend the stories of #Tokyo Apartment to people studying Japanese language. Any one of them might be good for inclusion on the syllabus of an upper-level Japanese language class. In particular, the first and final stories of the collection are short, amusing, and easy to understand from context clues, and I imagine that either of them would be a nice treat for anyone just starting to read Japanese fiction.