In the woods, there is a castle. The castle was once the residence of the landowning family that ruled the area. During the war, it was the headquarters of a resistance movement. Now it sits empty and abandoned. The castle is so deep in the woods that most people couldn’t find it if they tried. No one tries, however, as the woods are filled with child-snatching imps. Strange noises come from the woods, and occasionally strange people as well.

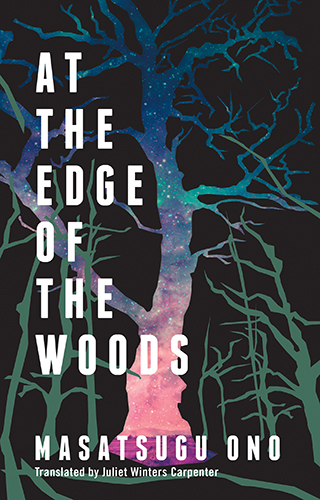

Masatsugu Ono’s At the Edge of the Woods is a novel about dread and anxiety. There’s no plot, nor is there any sort of story. Instead, Ono presents four episodes in the life of a father left alone with his young son while his wife is away. There’s no chronological order to the four chapters, which all occur at roughly the same time, and there’s no meaningful change in the personalities of the characters. Rather, the story development involves the slow intensification of an atmosphere of foreboding.

The nameless father who serves as the narrator is Japanese, as is his wife, who is pregnant with their second child. The wife has flown back to Japan to visit her parents, leaving her husband and son in an unspecified European country that reads as Germany-coded. The family has taken up residence at the eponymous edge of a vast forest in a rural area dotted with small towns.

The country is now at peace, but its neighbors are not so lucky. Long lines of refugees stream across the borders, seemingly unhindered by local authorities. It’s entirely possible that some of these refugees have camped out in the woods next to the narrator’s house, but it’s difficult to say for sure. It’s equally difficult to specify the origin of the odd sounds constantly emerging in the forest.

Characters drift in and out of the narrative, leaving behind very little of themselves save for strong emotional impressions. The disabled daughter of a bakery owner has good intentions but struggles to make herself understood. The postal worker who delivers the mail relates grotesque stories to the father, who suspects the man might be reading and discarding his wife’s letters. A neighboring farmer has always been kind to the narrator’s family, but his son reports that he once saw the man tie a dog in a burlap sack and beat the poor creature to death.

Perhaps the most striking of these characters is an elderly woman that the narrator’s son invites into the house. She appears seemingly from nowhere, and she vanishes just as mysteriously. While she’s in the house, though, she becomes a living symbol of the narrator’s anxieties regarding his ill-fitting role as the solitary caretaker of a young child in a foreign land:

Overcome, the old woman buried her face in her hands. She trembled violently, and a sob escaped her. I looked up. The kitchen windows were all closed. And yet in the air there hovered the sour smell of decayed leaves from deep in the woods, leaves that would never dry out. Steam rose from the old woman. The steam was not from her tea. A puddle spread at her feet. (20)

In his “Introduction” to The Oxford Book of Gothic Tales, Chris Baldick neatly summarizes the genre as an expression of the fear that the horrors of prior eras will not remain comfortably in the past. At the Edge of the Woods presents the readers with a range of Gothic tropes to heighten the sense of uneasy suspicion that, even in the most progressive of European countries, there is no escape from misery and cruelty. While the back-cover copy of At the Edge of the Woods calls the novel “an allegory for climate catastrophe,” this feels like a bit of an interpretive reach. Instead, Ono seems to be suggesting more broadly that, even in our bright society sustained by futuristic technologies, we’re never that far away from the edge of a large and unknowable forest.

At the Edge of the Woods can be difficult to read, and it’s probably not for everyone. Speaking personally, though, I love this book, and I’ve read it on the winter solstice every year since it was published in 2022. Ono’s writing is gorgeously atmospheric, and the legendary Juliet Winters Carpenter has done a dazzling job with the translation. If you appreciate the sort of quiet, eerie, and darkly suggestive Japanese Gothic writing typified by Yoko Ogawa’s short story collections Revenge and The Diving Pool, I’d recommend At the Edge of the Woods as the next step on a shadowed path into the liminal spaces in the penumbra of modern civilization.