A young woman named Kiyose was recently promoted to the position of manager at an independent café. She devotes her love and attention to the business, but all is not well. One of her employees is a constant source of frustration, and she hasn’t spoken to her long-term boyfriend Matsuki since they had an argument about how Kiyose should handle the situation.

One day, Kiyose randomly gets a call from the hospital informing her that Matsuki is in a coma. The nurse in charge of his care informs her that she’s the closest thing he has to a next of kin, so she dutifully goes to confirm his identity. During her visit, Kiyose learns that Matsuki suffered a head injury sustained under mysterious circumstances, and his only other visitors are two unrelated people she’s never met.

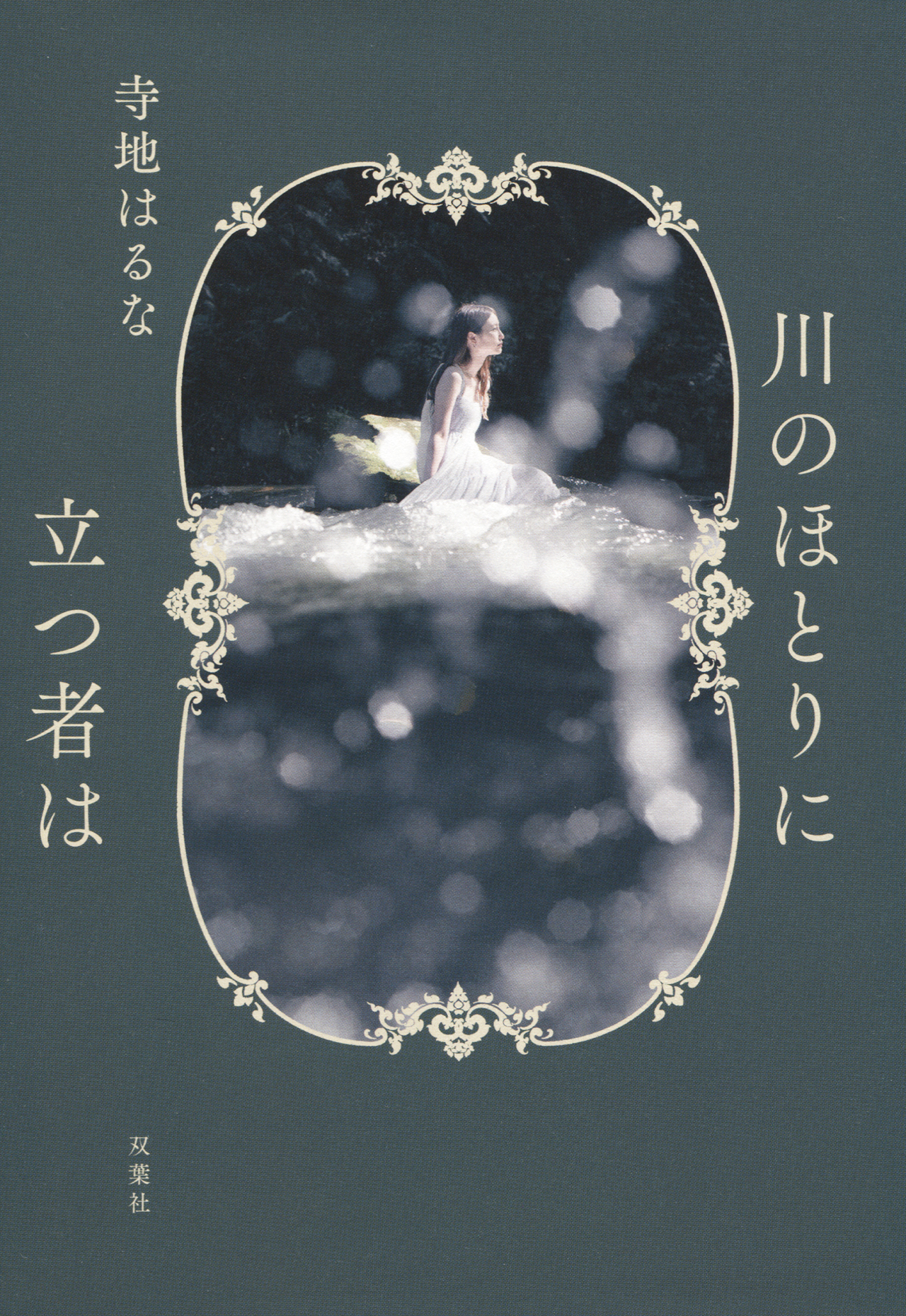

川のほとりに立つ者は initially seems as though it’s going to be a mystery about crime, but it’s actually a character drama about living with invisible disabilities, specifically ADHD and dyslexia. As Kiyose begins digging into Matsuki’s life, she learns that, despite being alienated from his uptight family of professional calligraphers, Matsuki was teaching an adult with dyslexia how to write so that he could pass letters to a woman trapped in an abusive housing situating.

The novel’s title is taken from the proverb 川のほとりに立つ者は水底に沈む石の数を知り得ない, “Those who stand on the river’s shore can never know the number of stones under the water.” After learning about the discrimination faced by Matsuki’s friend, however, Kiyose begins to understand how unfair it is to tell someone with a disability that they’re just being lazy and irresponsible. She realizes that she was being cruel to her employee, who had come out to her as having ADHD, and she resolves to make her café a more accessible and welcoming space while being kinder to the people in her life.

Although her work hasn’t yet been translated into English, Haruna Terachi is a prolific writer who has won a number of literary prizes since her debut in 2014. This is my first encounter with Terachi’s writing, and I enjoyed this short novel, especially the chapters that were narrated from Matsuki’s perspective. I also found it satisfying to watch the mysteries presented at the beginning of the story slowly unravel. That being said, I was unsatisfied with the novel’s conclusion that the solution to systemic discrimination falls on individuals, who simply need to “walk at the same pace” as people with disabilities.

Still, it’s always good to see sympathetic stories about disability – especially invisible disability – and I appreciate Terachi’s pushback against the toxic misconception that disabled people simply aren’t trying hard enough. Along with people interested in the experience of living with disability in contemporary Japan, I’d recommend this book to anyone looking for a fast-paced and wholesome character drama driven by hidden secrets brought to light.