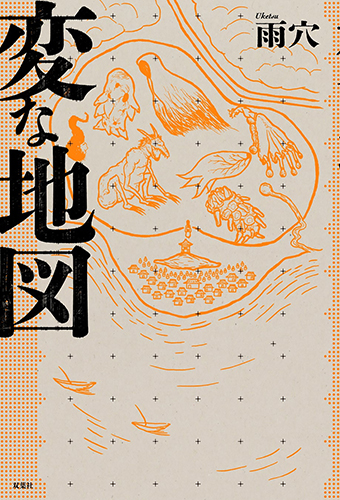

Strange Map (変な地図), published in October 2025, is the fourth book written by Uketsu, the bestselling author of Strange Pictures and Strange Houses. Unlike Uketsu’s previous books, which are collections of seemingly unrelated stories eventually connected by an overarching narrative, Strange Map is a proper novel that follows the actions of a single protagonist, Uketsu’s architect friend Kurihara from Strange Houses. Despite its more conventional narrative format, Strange Map is still filled with Uketsu’s characteristic illustrations and diagrams, which aid the reader in visualizing the uncanny spaces of its horror-themed mystery through a remarkable set of twists and turns.

Strange Map opens with the written confession of an elderly woman named Kimiko Okigami. In her youth, she writes, she took the lives of countless people. Before she dies, she wants to tell the story of the village where she was born and its neighboring mountain, which was supposedly inhabited by demons.

The next section raises the stakes even higher. In the present day of July 2015, Kōsuke Ōsato wakes up after a night of drinking to find himself lying in a train tunnel. He recognizes the tunnel immediately, as he’s the president of the railway company that constructed it. The tunnel has emergency exits, of course, but there’s just one problem – he’s right in the middle between two of them, and the first train of the morning should be coming any second now.

After thoroughly grabbing the reader’s attention, Strange Map shifts to the perspective of its main narrator, a 22yo college student in Tokyo named Fuminobu, who usually goes by his family name of Kurihara. Kurihara is an architecture major who’s currently on the job market, but he hasn’t had any luck so far. This is likely because, as he readily admits, he’s terrible at interviews. When asked why he’s interested in architecture, for instance, he can’t quite bring himself to admit that he wants to follow in the footsteps of his mother, who once played games with him involving engineering problems but died when he was still a child.

After yet another unsuccessful round of interviews, Kurihara’s sister asks him to come home and visit his father, who needs to talk with him. This conversation ends up being about the house left behind by Kurihara’s grandmother – the woman who wrote the letter that opens the novel. Before his father sells the house, Kurihara asks to see it for himself, and he discovers a notebook containing a set of burned photos alongside the “strange map” of the title, which depicts a seaside village below a mountain filled with monsters.

Like his late mother, Kurihara can’t sleep easy until he’s solved the problem in front of him. His father gives him permission to investigate, but only on the condition that he solves the family mystery in time to return home and do practice interviews with his sister before his next real interview, which is only a week away.

Interspersed between chapters, his grandmother’s letter continues. She writes of her hometown of Kasōko, an isolated village surrounded by the sea on one side and forest on all others. While the men caught and sold fish, the women handled the business of maintaining the village itself. Among other things, this maintenance involved carving stone statues to ward off the demons of Mojōyama, the mountain looming over the village.

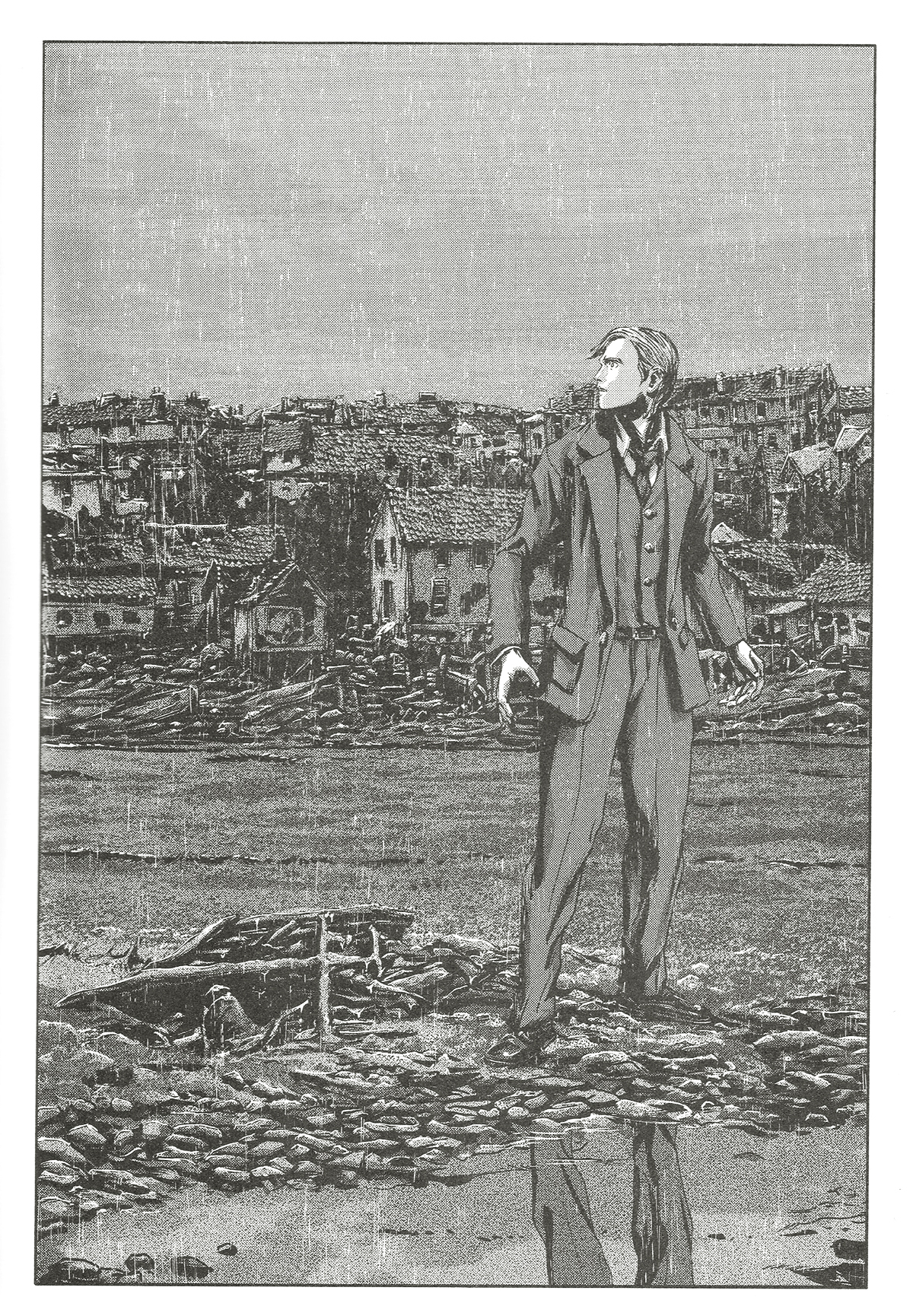

Kurihara, who doesn’t know any of this history, nevertheless manages to ascertain the location of the village. He travels to the rural seaside only to find that the village was completely abandoned decades ago. To complicate matters, he finds himself smack in the middle of a scandal surrounding the succession of Kōsuke Ōsato, the president of the local railway company who was mysteriously run down by one of his own trains.

Was the death of the railway president truly an accident, or was it murder? What happened to Kasōko village? Who exactly did Kurihara’s grandmother kill – and what are the demons on the mountain?

To help the reader visualize the specifics of the story, Uketsu has provided all manner of simple diagrams illustrating how the space of the narrative is laid out. These visual inserts were necessary in Strange Pictures and Strange Houses; meanwhile, in Strange Map, they’re largely superfluous. The reader probably doesn’t need a visualization of the concept that “there are five equidistant emergency exits in the train tunnel,” for example. Uketsu has also provided slightly silly diagrams of various social relationships, such as an illustration of the railway company president wearing a suit and sitting at a desk while his second-in-command wears a construction helmet and manages a job site.

Still, I’m not complaining. Regardless of whether they’re necessary, I love all of these illustrations. I find their lo-fi clunkiness charming, and the space they create on the page helps to set the pace of the story. It would be all too easy to fly through this book, but the illustrations helped me slow down and focus on details. In addition, I found that the “unnecessary” illustrations help to reveal the inner workings of the narrator’s mind.

To me, Kurihara reads as being on the autism spectrum, an aspect of the character that contributes to the distinctive narrative style of the story. The closest comparison I can make is to Sayaka Murata’s Convenience Store Woman, but there are echoes of Mark Haddon’s The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time as well. Although he doesn’t identify as autistic, Kurihara understands that he needs to work on his people skills, and the secondary B-plot of the novel involves his carefully considered approach to teaching himself to behave “normally” instead of immediately saying something that’s true but will hurt other people’s feelings.

I’m used to Uketsu’s characters behaving like chess pieces on a game board, so this added depth of character came as a pleasant surprise. Also, while I usually read mystery novels for the pleasure of watching fictional characters die in ridiculous ways, I found myself feeling invested in Kurihara’s safety, as well as his emotional wellbeing. This attachment to the character adds yet another layer of tension to the story as Kurihara becomes personally involved with the family that runs a local inn.

Strange Map is a super fun and fantastically clever mystery novel, and its elements of gothic horror are as darkly brilliant as anything written by Edgar Allan Poe or Arthur Conan Doyle. Jim Rion has done a marvelous job with the translations of Strange Pictures and Strange Houses, and I’m looking forward to what he does with Strange Map. For the time being, the sequel to Strange Houses, which is titled Strange Buildings in English, is scheduled to be published in March 2026, so that’s something to look forward to as well.

It’s a great time to be a fan of Japanese mystery novels, and I’m interested to see how Uketsu’s work in translation might influence other authors. Do I want to see Uketsu copycats? Sure! Absolutely. But do I also want to see a generation of writers raised on YouTube creepypasta take inspiration from Uketsu and translate that sort of multimedia textual fragmentation into a new style of fiction? Hell yes. Let’s go.