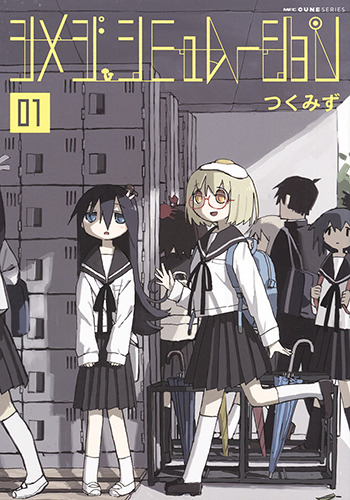

Shimeji Simulation (シメジ シミュレーション) is a gentle but deeply surreal slice-of-life manga about two teenage girls living through the end of the world – or perhaps not “the” world, necessarily; but rather, an artificial world that they happen to inhabit. The focus of the manga isn’t on the apocalypse, which passes mostly unremarked and unexplained. Instead, the core of the story is the friendship (and understated romance) between the two girls, Shijima and Majime.

Shijima Tsukishima has spent the past two years of middle school quietly living inside a closet, and the manga opens when she decides to begin attending high school at the beginning of the school year. Why Shijima became a hikikomori is something of a mystery, but her primary personality trait is that she dislikes being bothered. She plans to spend her time in high school silently reading books at her desk.

This plan is interrupted by a classmate named Majime, who aggressively demands that Shijima become her friend. Since a pair of shimeji mushrooms sprouted from the side of Shijima’s head during her period of isolation, Majime immediately gives her the nickname “Shimeji,” an appellation that quickly becomes as pervasive and persistent as Majime herself.

Majime bluntly inserts herself into Shijima’s life and persuades her to join the school’s Hole Digging Club, which is managed by an art teacher named Mogawa. Majime assumes that the club is little more than an excuse to hang out after school, but Mogawa is oddly committed to the endeavor, especially when encouraged by the quiet presence of a second-year student named Sumida who only communicates through abstract drawings. Meanwhile, Shijima’s older sister has dropped out of college to devote herself to the ongoing construction of a bizarre machine with an inexplicable function.

For the most part, the girls engage in mundane slice-of-life adventures. They chat in the classroom, visit one another’s houses, and attempt a study session at a family restaurant. Mogawa teaches her art lessons. Majime catches a cold. A group of girls in their homeroom start a rock band. Shijima meets a super-senior named Yomigawa who’s decided to stay in high school just to hang out in the library and read philosophy books.

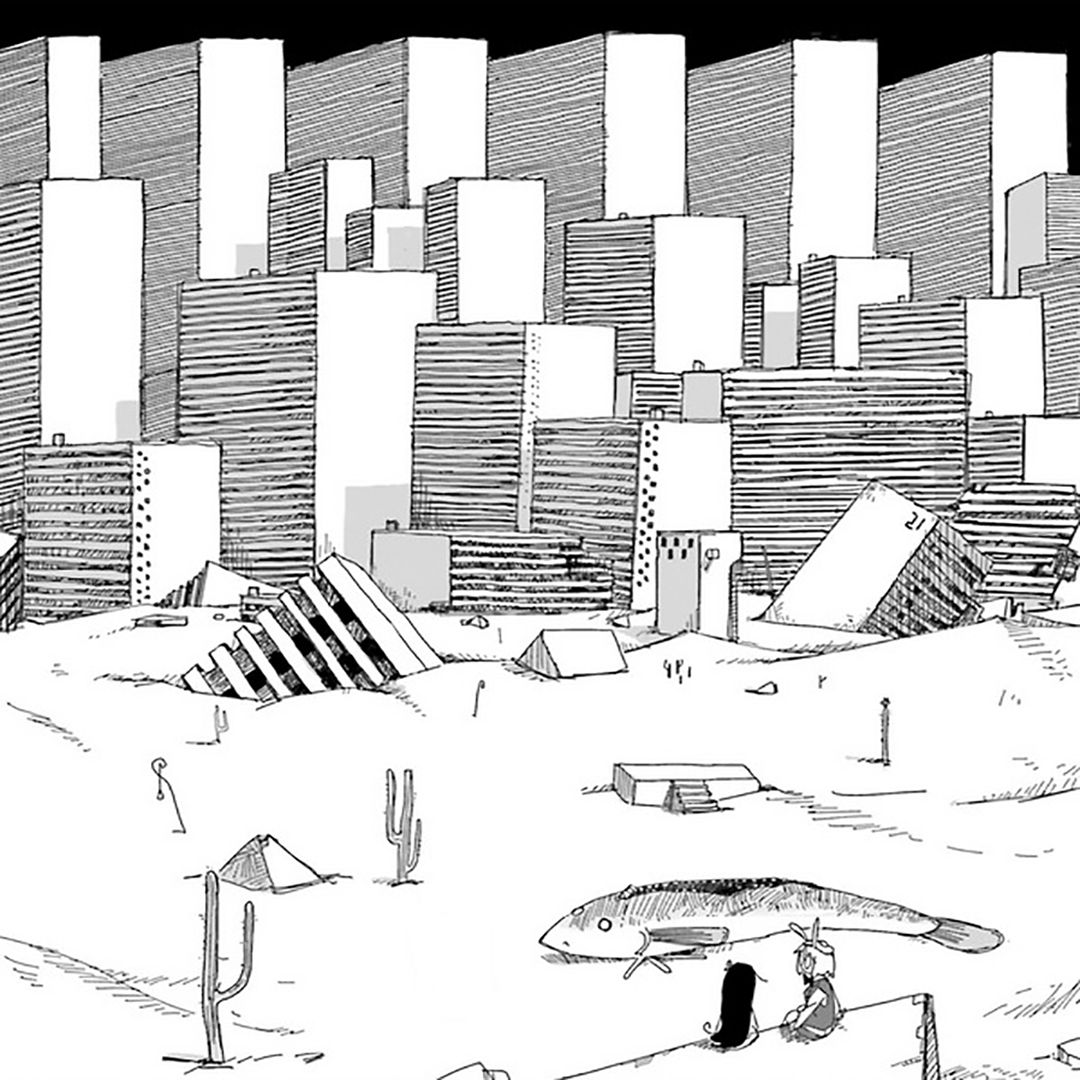

What makes this manga interesting are the strange glitches in the world surrounding the characters. The mushrooms sprouting from Shijima’s head are a good example, but there’s also the fact that Shijima and her sister occupy one of the only two tenanted apartments in a giant danchi housing building that’s falling apart yet still somehow livable.

As the story progresses, more glitches begin to manifest. Everyone wakes up to a snowstorm in the middle of summer, for example. One day, the school building is flipped vertically and becomes a pocket dimension with a separate axis of gravity. Another day, water loses its mass and floats in the air. Suburban streets twist into optical illusions, and fish swim through the sky.

Although small glitches seem to be innate to the world, they’re exacerbated by Shijima’s sister, who’s been building and experimenting with various devices that alter the fabric of reality. Each of the first three volumes of the manga concludes with a longer narrative segment that shows the consequences of these experiments for Shijima and Majime, who are briefly thrown into the gaps between the cracks of reality.

The cumulative damage caused by Shijima’s sister is countered by a godlike entity who presents as a young girl and calls herself “the Gardener.” The Gardener’s role is to ensure that the reality experienced by the characters doesn’t mutate too wildly from one day to the next, but her power is curbed by the features of the universe’s code intended to keep its residents safe. She might be able to repair gaps in reality, but she has no means of forcing her will onto humans, even if it’s for their own good.

Like Tsukumizu’s previously serialized manga, Girls’ Last Tour, it’s difficult to say that Shimeji Simulation is “about” anything. There’s no plot to speak of, and the only real conflict is between the characters and the entropy eating away at the edges of their slowly decaying world. In addition, it’s never explained how this constructed universe and the characters who inhabit it came to exist. Instead, I think it’s probably fair to say that the manga’s primary concern is existential ontology. In other words, what does it mean to be human, and why do we exist?

I recently read an interesting essay (here) whose author argues that Shimeji Simulation is about the barriers between people, why we need them, and what happens when they disappear. If everyone were able to get exactly what they want, what happens when the desires of separate individuals come into conflict? If there were a world perfectly tailored for one person alone, could anyone else live there? And, if you retreat into complete solipsism, what’s the point of being alive?

Toward the end of the manga, Shijima finds herself in a situation very much like her self-imposed hikikomori isolation in the beginning, when she lived entirely in the darkness of her closet. In the simulated world she comes to occupy through her sister’s rewriting of the universe’s code, Shijima doesn’t bother anyone, and she never has to deal with any external input that she doesn’t choose for herself. Still, can we really say that such pristine loneliness is preferable to the messiness of human relationships?

I read Shimeji Simulation as a story about the various ways that people communicate and connect with one another. Shijima never becomes a “normal” or friendly person, but she still manages to find joy and meaning in her interactions with other people, even if most of these interactions are nothing special. This is why, in the fifth and final volume of the manga, Shijima breaks the boundaries of her personal universe to find Majime, wherever her friend might exist in the fractured constellation of simulations.

“The meaning of life is to understand love” may seem cliché; but, given how strange and surreal her story becomes, Shijima’s realization feels significant and well-earned. Life is a constant shifting and melding of interpersonal boundaries, and communication and companionship are worth the pain and trouble of being human.

Shimeji Simulation is a remarkable work of science fiction. The manga may seem to have an unassuming beginning, but its narrative structure gradually builds, loops back in on itself, and continually starts over from a weirder and more nuanced position. Likewise, Tsukumizu’s art may initially feel sketchy, but this style is perfectly suited to express the uncanny glitches and fluid malleability of the setting. Shimeji Simulation is gentle and quiet, but also immensely intelligent and creative, and it’s a manga to contemplate and enjoy slowly while allowing yourself to be transformed alongside the characters and their strange but fascinating world.

Shimeji Simulation hasn’t received an officially licensed English translation, but a fan translation is currently available to read on Dynasty Scans (here). If you’re interested in a small taste of the manga’s tone, I’d also like to recommend the short fan anime adaptation of the opening chapter on YouTube (here).