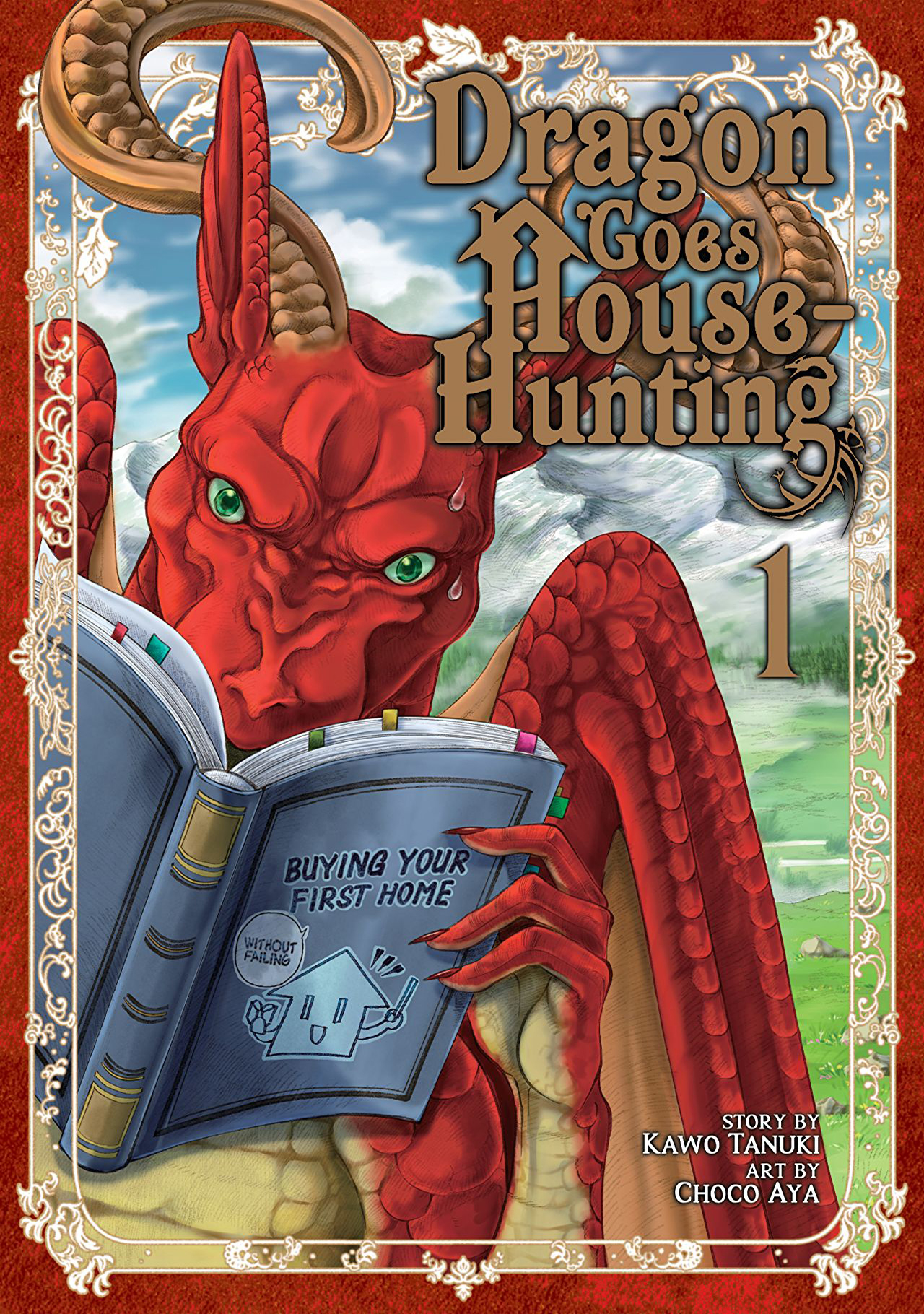

Cats are adorable creatures, it’s true. It’s also true that they’re a little magical. Unfortunately, the experience of caring for a cat isn’t all sunshine and rainbows, and there’s a lot of cleaning involved. Mayumi Inaba’s autobiographical essay collection Mornings With My Cat Mii is a beautifully written attempt to capture the not-always-rosy reality of sharing your space with a cat while doing your best to manage your life as a human.

In the summer of 1977, Inaba follows the cries that drift in through her window and discovers a ball of fluff stuck at the top of a fence along the bank of the Tamagawa River in western Tokyo. Since it’s freezing outside, she takes the kitten home. Inaba names her “Mimi,” or “Mii” for short, after her constant crying. Despite her precarious childhood, Mii goes on to live for almost twenty years, accompanying the author through major developments in her personal life and career.

Mayumi Inaba (1950-2014) worked in a number of creative industries while publishing stories, essays, and poetry. The opening essays in Mornings With My Cat Mii are about the milestones in Inaba’s life as she divorces her husband in Osaka to focus on her career in Tokyo. As time passes, Inaba begins to devote more attention to her friendships and psychological wellbeing, a shift in priorities represented by her growing love for Mii.

Mornings With My Cat Mii is far from wholesome, however. Inaba is nothing if not honest about the vicissitudes of life. Sometimes you and your partner grow distant. Sometimes you get kicked out of your house by your landlord. Sometimes people abandon animals. And sometimes you have to bear witness to your pet’s slow decline toward death.

A major element of Inaba’s commitment to honesty are her raw descriptions of the mess of keeping an animal in your house. Sometimes, for example, your entire apartment is going to smell like cat urine. Sometimes you have to scrub puke out of the carpet. Sometimes you have to extract your cat’s feces with your own hands.

Regardless, Inaba always finds a silver lining and an interesting story to tell. I especially enjoyed her essay “The Pet Sitter,” which provides an intriguing glimpse into the thriving industry of petcare services in Japan while digging its heels into the silliness of celebrity pet therapists. I also love “The Winter Break,” which describes a trip Inaba took to the countryside with her sister so Mii could touch grass and frolic in nature. The essay “Moving House” stands out as a playful description of a typical day in young Mii’s life in Inaba’s old house in the west Tokyo suburbs, which were still filled with pockets of nature in the 1970s.

Each essay is less than ten pages long, and most of them feature several verses of a poem as a postscript. Ginny Tapley Takemori has done a marvelous job translating Inaba’s poetry. Just be aware that some of these poems might make you a bit misty-eyed, especially if you’re feeling sentimental about the death of a pet of your own.

I’m generally not a fan of Japanese cat books, but Mornings With My Cat Mii isn’t bubblegum pop about how all of life’s problems can be magically solved by a cat. Rather, this is messy and honest nonfiction about the hardships of pursuing a creative career as a single woman. Still, Inaba manages to find moments of sweetness in life, which she generously shares with the reader in her soft and shining prose.