This past semester I taught a class on Japanese science fiction and fantasy, and I was surprised by how interested my students were in learning more about the social and cultural context of contemporary Japan. I therefore put together a list of recommendations for popular-audience books that are smart and specific yet still accessible to a casual reader. I decided to share this list here with the hope that it might prove useful outside the classroom.

If you’re interested in social issues facing contemporary Japan…

Dreux Richard’s Every Human Intention: Japan in the New Century (2021) tackles two of the most significant demographic concerns in Japan, immigration and rural depopulation, as well as a major environmental concern, Japan’s aging nuclear reactors. Richard approaches these topics by conversations with people who are directly involved, from Nigerian immigrants to census workers to nuclear regulatory officials. The writing is remarkably rich and features a large cast of characters with interlocking stories.

If you’re interested in learning more about the “Triple Disaster” of March 2011…

Richard Lloyd Parry’s Ghosts of the Tsunami: Death and Life in Japan’s Disaster Zone (2017) tells the stories of people who survived, as well as the stories of people who didn’t. There are elements of true crime in Parry’s journalism, which seeks to understand what happened, how it happened, and how it affected those involved. Parry is never needlessly dramatic or unkind, but he is justifiably critical of the decisions of elected officials at all levels of government.

If you’re interested in a deep dive into the “Lost Decade” of Japan in the 1990s…

John Nathan’s Japan Unbound: A Volatile Nation’s Quest for Pride and Purpose (2004) was written at a time when people were just beginning to understand the causes, repercussions, and long-term effects of Japan’s prolonged economic recession. Although it was published almost twenty years ago, this book remains relevant. Nathan is a professor and a literary translator, and reading each chapter is like listening to a fascinating class lecture.

If you’re interested in the dark side of Japan’s postwar economic miracle that emerged in the 1980s…

Norma Field’s In the Realm of a Dying Emperor: Japan at Century’s End (1991) is simultaneously an academic study and an intensely personal memoir. It’s also a genuine work of literature, and it won an American Book Award in 1992. Field’s prose is impeccably beautiful and a true pleasure to read, and her critique of the rise of neoliberal capitalism in Japan is penetratingly sharp. This book doesn’t feel the least bit dated, and it’s actually somewhat uncanny how all of Field’s predictions for Japan’s future came true.

If you’re interested in the history of how Japanese pop culture has been exported and received in the United States…

Matt Alt’s Pure Invention: How Japan’s Pop Culture Conquered the World (2020) is recounted from the perspective of an active working professional in the field of cultural exports from Japan. Alt begins in the immediate postwar period, and the scope of this book is impressively expansive. Alt regularly writes intriguing longread pieces for the New Yorker, and his 2018 essay “The United States of Japan” is a fascinating preview of an equally fascinating book.

If you’re interested in the American anime explosion during the early 2000s…

Roland Kelts’s Japanamerica: How Pop Culture Has Invaded the U.S. (2006) feels charmingly retro in its perspective on Japan’s anime industry, especially when it comes to Kelts’s optimistic enthusiasm. This book captures the excitement of the mid-2000s anime boom fueled by DVD sales and anime conventions, which were springing up like mushrooms in North America. Kelts hits all the high points of the conversation at the time as he discusses topics ranging from anime auteurs to otaku fandom subcultures.

I also want to mention Jonathan Clements’s Anime: A History, which was published in 2013 by the British Film Institute. This is a muscular book that might be a bit too powerful for a casual reader, but it’s exquisitely well-researched and absolute required reading for anyone’s who’s serious about studying anime in the context of the creative industry that produces it.

If you’re interested in how the gaming industry developed in America during the 1980s through the 2000s…

Jeff Ryan’s Super Mario: How Nintendo Conquered America (2012) is a lot of fun. Very few people knew how to write about video games back in the early 2010s, but Ryan has perfect pitch. Nintendo is an apt focus of Ryan’s exploration of how the gaming industry underwent numerous rapid shifts during a twenty-year period, but the book is still interesting and accessible even to people who don’t particularly care about Nintendo games.

If you’re interested in landmark speculative fiction and sci-fi anime from the 1980s and 1990s…

Robot Ghosts and Wired Dreams: Japanese Science Fiction from Origins to Anime (2007) is an academic essay collection, but most of the essays are fun, interesting, and easy to read. There’s a lot of intriguing analysis here, as well as a great deal of literary and media history that you can’t find in English anywhere else.

If you just really love Hayao Miyazaki…

Helen McCarthy’s Hayao Miyazaki: Master of Japanese Animation (1999) is a classic, with beautiful summaries, insights, formatting, and screenshots. Susan Napier’s essay collection Miyazakiworld: A Life in Art (2019) is published by an academic press but still accessible and enjoyable, and it has the added bonus of covering Miyazaki’s manga in addition to his films.

If you’d like to do some armchair tourism of otaku subcultures in Tokyo…

Gianni Simone’s Tokyo Geek’s Guide: The Ultimate Guide to Japan’s Otaku Culture (2017) is filled with incredible photos and a wealth of interesting recommendations. It also includes several illustrated essays on the history and cultural context of various subcultures, from comics to cosplay to pop idols to anime musicals.

If you want to learn about Japanese folklore while doing some armchair tourism of rural Japan…

Cécile Brun and Olivier Pichard’s Onibi: Diary of a Yokai Ghost Hunter (2016) is a collection of comic nonfiction essays about the artists’ travels to various points of interest in the Tōhoku region of north Japan. There is indeed ample discussion of ghosts and yōkai, but this book’s true charm is its depiction of small rural towns and the colorful human characters who live there.

If you want to learn about Japanese urban legends and the true stories that inspired them…

Tara A. Devlin’s Toshiden: Exploring Japanese Urban Legends (2018) is self-published on Amazon, but that doesn’t make it any less well-researched. This book covers many internationally well-known Japanese urban legends, as well as a few that are infamous in Japan but aren’t yet widespread on the English-language internet. It’s much longer and denser than you might expect, but every chapter is extremely entertaining.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

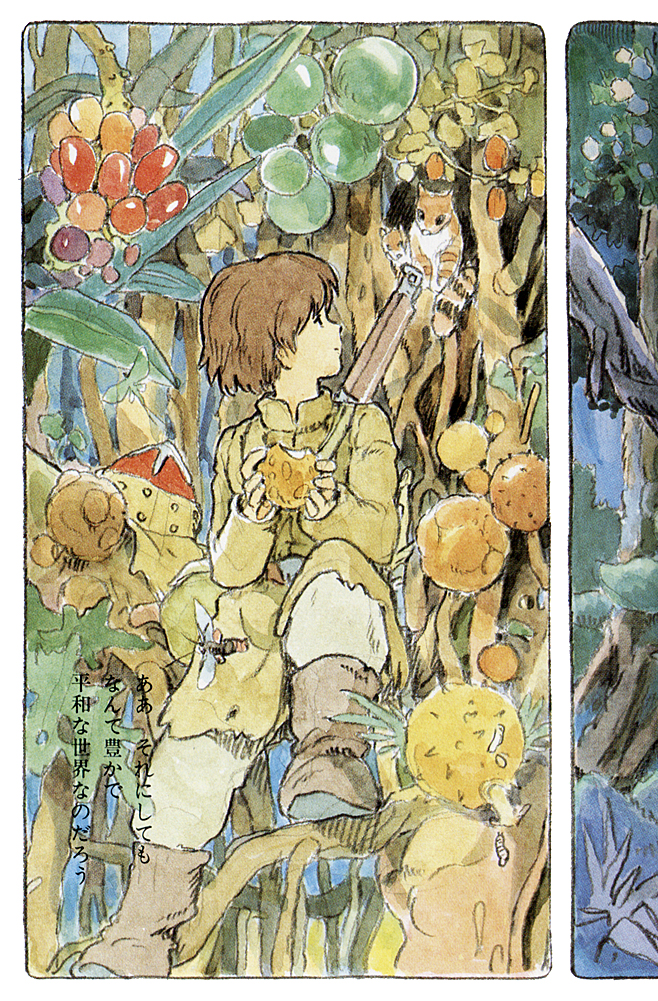

This post’s header illustration was created by Marty Tina G., who goes by @geezmarty on Twitter. You can check out their portfolio (here) and download their short fantasy and sci-fi comics (here). Marty is an expert at bold character designs and bright color palettes, and I trusted them to capture the energy and excitement of reading an interesting book that expands the world.