Machiko Kyō’s Kamimachi (かみまち) was serialized from June 2019 to December 2022 and published as a two-volume graphic novel in August 2023. The story follows four homeless teenage girls who find themselves at a privately run youth shelter called Kami No Ie (“Family of God”) in the Tokyo suburbs.

Although he initially seems kind and welcoming, the middle-aged man who runs this shelter is a sexual predator, and he has assaulted and murdered one of his young charges prior to the beginning of the story. The ghost of this young woman, in the form of a Christian angel, helps the girls find the courage to escape the Kami No Ie shelter.

Each of the four main characters in Kamimachi has become homeless after escaping a toxic home environment.

Uka is the only child of a single mother who projects her loneliness and frustrated ambitions onto her daughter. The story begins as Uka leaves home and seeks shelter by means of a roomshare app. After a number of awkward situations, Uka comes to the attention of a group of men who use the app to recruit sex workers. These men force Uka into a situation in which she’s expected to trade a night at a short-term rental space for sex. She breaks out of the apartment and wanders the streets of Tokyo before finding herself at the Kami No Ie shelter.

Uka’s closest friend at the shelter, Nagisa, has been sexually abused by her stepfather for years. She finally flees from home after her mother witnesses one of these assaults and turns away in disgust.

Arisa was raised as a television idol by a single mother. After her mother’s sudden death in an accident, Arisa is given to the care of a talent manager who steals her inheritance and financial assets, leaving her destitute.

Yō is one of five siblings. She’s so neglected by her family and bullied by her brothers that she finds it preferable to sleep in subway stations. Eventually she stops returning home altogether.

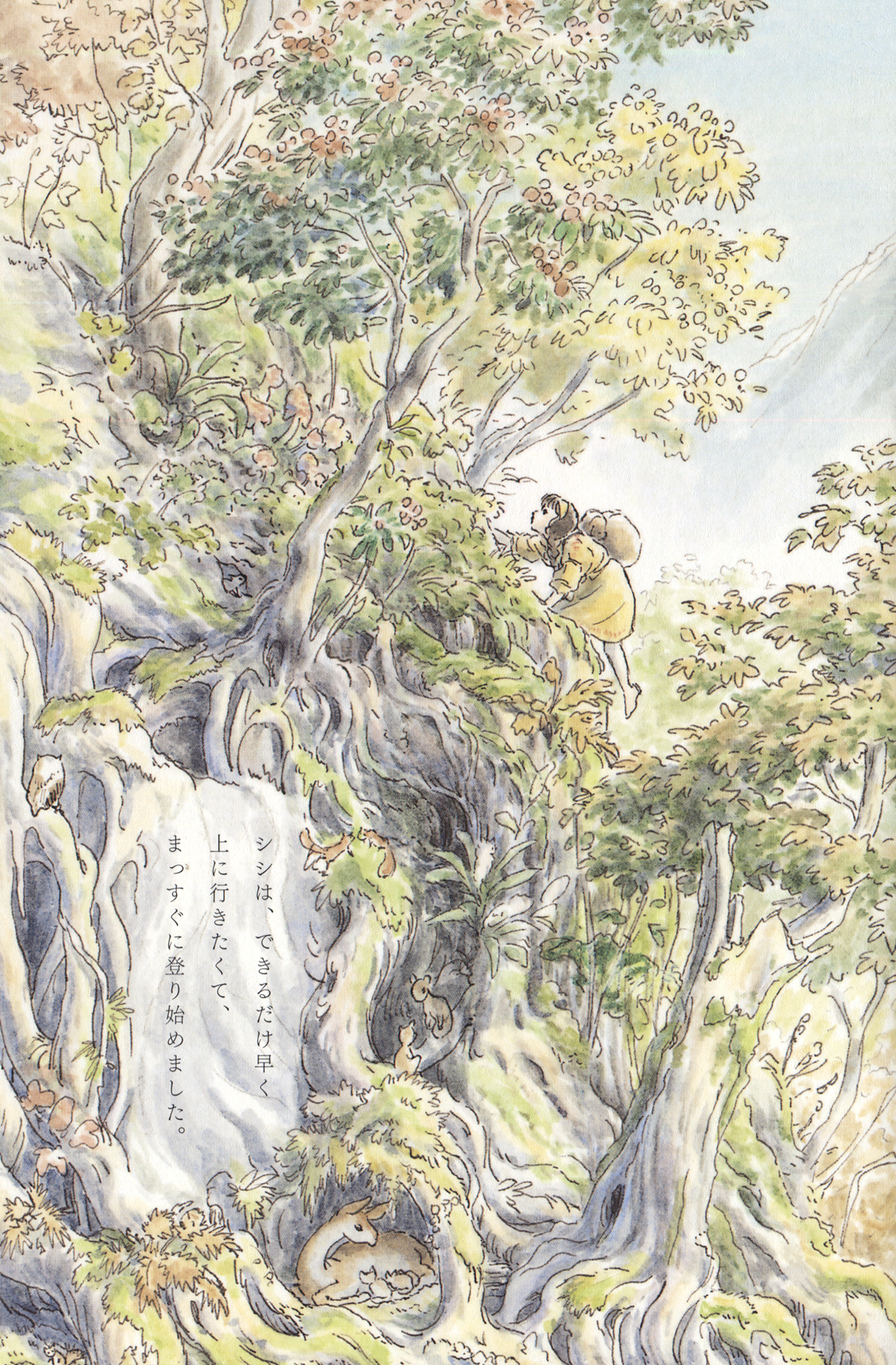

For each of these young women, Tokyo becomes a wilderness whose anonymous open spaces serve as a refuge from the enclosed interiors where they’re coerced into enduring abuse. Kyō draws indoor scenes using small panels with blank backgrounds, and these scenes often feature close-ups of the characters’ faces in moments of distress. Meanwhile, Kyō depicts outdoor scenes with large panels that frame the characters with trees and buildings. The expansive outdoor settings often serve as the stage for small moments of kindness and emotional clarity.

In Chapter Three, for example, Uka flees into the night after an attempted sexual assault at a roomshare apartment. After her escape, she wanders through the rain with nothing but the clothes on her back. Out of context, the rainy cityscape may seem bleak, but the large panels filled are a visual relief after the oppressively small and claustrophobic panels that depict the apartment.

One of the anonymous figures passing in the rain, whom the reader later learns is Yō, stops beside Uka to give her an umbrella. Page 71 opens with a close-up of Yō’s extended hand before spreading into an open panel in which Uka and Yō stand at the center of a composition framed by misty buildings and puddles on the concrete. The two small figures reaching out to one another are enclosed in a soft curtain of rain, and the sense of relief at being a part of a larger world is palpable.

Chapter Seven contains a similar scene in which the open sky and background cityscape suggest freedom from the violence that occurs behind closed doors. Nagisa, who’d encountered Uka in a roomshare arrangement, takes Uka’s discarded uniform and attends school in her place. One of Uka’s former classmates approaches Nagisa, offers to share her lunch, and asks that Nagisa talk with her on the roof. Nagisa initially tries to be normal, showing the girl photos of her mother and stepfather’s new infant daughter.

During this scene, the panels become progressively smaller until Nagisa finally admits the truth about having left her family. The shift to a full-page panel depicting the city’s jumble of buildings spreading under the open sky signals Nagisa’s admission that something has to change. This moment also serves as the catalyst for Uka’s classmate to begin searching for her missing friend, a decision that ultimately results in Uka’s rescue from the Kami No Ie shelter.

The openness of Tokyo cityscapes in these scenes suggests that the sort of hidden abuse endured by these young women needs to be brought into the open and exposed to the light of public scrutiny. Along those lines, I can’t help but feel that Kyō’s depictions of outdoor spaces in Kamimachi also reflect the artist’s emotional response to the Covid pandemic. For people in precarious situations, being physically stuck inside often exacerbated the experience of feeling trapped within oppressive social systems.

As an artist who documented the pandemic years through evocative illustrations posted to Instagram, Kyō’s project is not simply to depict the beauty of architecture and greenery within the city, but also to comment on the importance of open outdoor “third places” for young people suffering from social pressure and economic strain. Kamimachi doesn’t provide easy solutions, but it’s cathartic to see the issue of youth precarity brought out into the open air.

Machiko Kyō is a prolific and award-winning artist whose illustration collections have been celebrated by The Comics Journal (here). If you’re interested in reading more about the artist’s work, I published a short essay on her 2013 graphic novel Cocoon – whose animated adaptation is scheduled to premiere on NHK in Summer 2025 – on Women Write About Comics (here). Here’s hoping that English-language readers will be able to experience Kyō’s compelling and thought-provoking work in the near future.