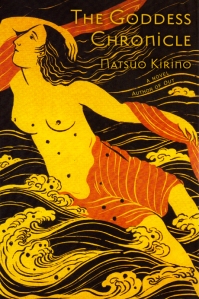

Title: The Goddess Chronicle

Japanese Title: 女神記 (Joshinki)

Author: Kirino Natsuo (桐野 夏生)

Translator: Rebecca Copeland

Publication Year: 2013 (America); 2008 (Japan)

Publisher: Canongate

Pages: 309

The protagonist of The Goddess Chronicle, Namima (“Woman-Amid-the-Waves”) lives on a small and richly vegetated island called Umihebi (“the island of sea snakes”). Umihebi is located somewhere in the island chain south of the kingdom of Yamato (i.e., Japan), and it is known throughout the Ryūkyū seas as a place where the gods come and go. The cape at the north end of the island is sacred and marked by a huge black boulder called “The Warning,” beyond which no one but the high priestess of the island may walk. On the eastern side of the island is the Kyoido (“Pure Well”), and on the western side is the Amiido (“Well of Darkness”), and only adult women are allowed to approach them. Between these landmarks grow plantain trees, banyan trees, pandan trees, and all manner of flowers. The water surrounding the island is filled with fish and sea snakes, which the island men take on their boats to trade with the people of other islands.

Namima’s grandmother, Mikura-sama, is Umihebi’s high priestess. She embodies the energies of light and life and protects the island from harm as she prays for prosperity. Because light and dark alternate, Mikura-sama’s daughter is dark, while Mikura-sama’s oldest granddaughter Kamikuu is light, thus entitling her to become the island’s next high priestess. If Kamikuu is light, then her sister Namima is dark; and so, if Kamikuu is to become then next high priestess of light and life, then Namima must become her dark counterpart, an outcast warden of darkness and death. While Kamikuu is fated to live at the top of a hill and be provided with generous quantities of nutrient-rich food as she prays to the gods and generates offspring from the seed of the young men on the island, Namima is fated to live in the shadow of a cliff, eating dregs and shunning the company of all save the corpses of the island’s dead, which she must watch decay in order to ensure that their souls pass on safely. Although Mikura-sama explains this to Kamikuu, the kind-hearted Kamikuu does not have the heart to tell her sister, so the teenaged Namima is outraged when she is hauled kicking and screaning down to a cave by the shore to take the place of Mikura-sama’s dark counterpart, who has vanished. Namima is immediately visited by her lover Mahito, the son of a family ostracized because of its matriarch’s inability to produce a female child, and the two escape the island on a small boat. Namima dies at sea, and that’s when the book really begins.

Namima, who dies with deep regret in her heart, is not allowed to move on to the world beyond death but instead finds herself in the underworld, a dark and formless landscape of unhappy souls presided over by Izanami, who is both a creator goddess and a goddess of death. Having died while giving birth to a fire god, Izanami found herself in the underworld. Her consort, Izanaki, came to retrieve her, but he was so appalled by the pollution and impurity of the underworld that he fled from his former lover and symbolically sealed the entrance to the underworld with a giant boulder. In her rage, Izanami vowed to end the lives of a thousand humans every day. In response, Izanaki vowed to erect a thousand birthing huts so that the human population would never decline.

Izanami, who has spent aeons under the earth, sees a kindred spirit in Namima and therefore draws Namima’s soul to her to act as an attendant and companion. The Goddess Chronicle is an account of how Namima rails against and finally settles into this role as she comes to understand and sympathize with Izanami’s suffering and the burden that the goddess has assumed. Over the course of her story, Namima returns to Umihebi as a tiger wasp and sees the religious and human drama of the island through the eyes of an outsider. Izanaki himself eventually enters the story and makes his own trip to Umihebi, so the reader sees the island from yet another perspective that further emphasizes how terrifying yet compelling its religious landscape and rituals are. The experiences both Namima and Izanaki have on Umihebi cause them to return to Izanami for closure and salvation.

In the end, however, there is no redemption for Izanami herself; there is only eternal hatred. I don’t want to give away certain plot developments; but, in light of these developments, it seems as if there would be so many other paths open to the goddess at the end of the novel. Moreover, although Namima can leave at any time, she decides to stay with Izanami, not as her friend or equal, but rather as the priestess of her pain. The novel ends with these lines, spoken by Namima:

I, who was once a priestess of the darkness, feel that serving here at Izanami’s side I am able to accomplish what I was unable to finish on earth. For, as I said earlier, Izanami is without a doubt a woman among women. The trials that she has borne are the trails all women must face. Revere the goddess! In the darkness of the underground palace, I secretly sing her praises.

I’m not sure if that’s a happy ending or not. So all women are united in a shared oppositional relationship to men? All women are united in their hatred, and in the fact that their destinies are shaped by the carelessness of men? Why do women have to harbor so much hatred? Why can’t men just be normal people instead of the shapers of the destinies of women? Why does there need to be an dualistic and antagonistic relationship between Woman and Man on such a deep mythical level?

In other mythological revisionist novels written from a feminist perspective, such as Margaret Atwood’s Penelopiad and Ursula Leguin’s Lavinia, there are layers of depth and meaning and subtle characterization added to mythological personages who were relatively flat in the original sources. In The Goddess Chronicle, the gods remain flat, and the human characters aren’t granted much depth either. The story told by the novel is fascinating, and the writing and translation are beautiful, but in the end there is almost no resolution or character development. Perhaps the point of the story isn’t to give human characteristics to nonhuman entities, however, but rather to provide the reader with an entryway into the conceptual geography of the existential questions religion and myth seek to address. In this latter purpose, The Goddess Chronicle succeeds spectacularly.

Kirino Natsuo is an extremely dark writer; and, while she never offers any feminist solutions to the problems she raises, she excels in bringing the reader’s attention to the sexism and hypocrisy that exist in mainstream narratives about women. By showing the reader the other side of the story, Kirino deftly illustrates the anger of the otherwise voiceless women who have been left out of most stories, but it is ultimately up to the reader to find hope in the situation and to figure out how to use her or his newfound anger to change the world for the better. In The Goddess Chronicle, Kirino encourages the reader to see one of the keystone tales of Japanese mythology from the perspective of darkness, and the perspective of those not showered with glory, and the perspective of those left behind. Such a perspective can be upsetting and frustrating, but it’s also an invitation to the reader to formulate her or his own interpretations, as well as her or his own ideas concerning the further adventures of these characters and their relevance to the modern world.